Seaweed, Ferns, and Sea Stars: The Fascinating World of Nature Printing

A conversation with Pia Östlund, co-author of Capturing Nature, about discovering an old art form, what it means to work on an enormous creative project, and the power of the natural world.

Creative Fuel is brought to life by paid subscribers. If you like getting this newsletter please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You help to keep the studio running and the coffee flowing! And you’ll be able to sign up for this month’s Studio Session, held on May 23rd.

How do we understand the world around us?

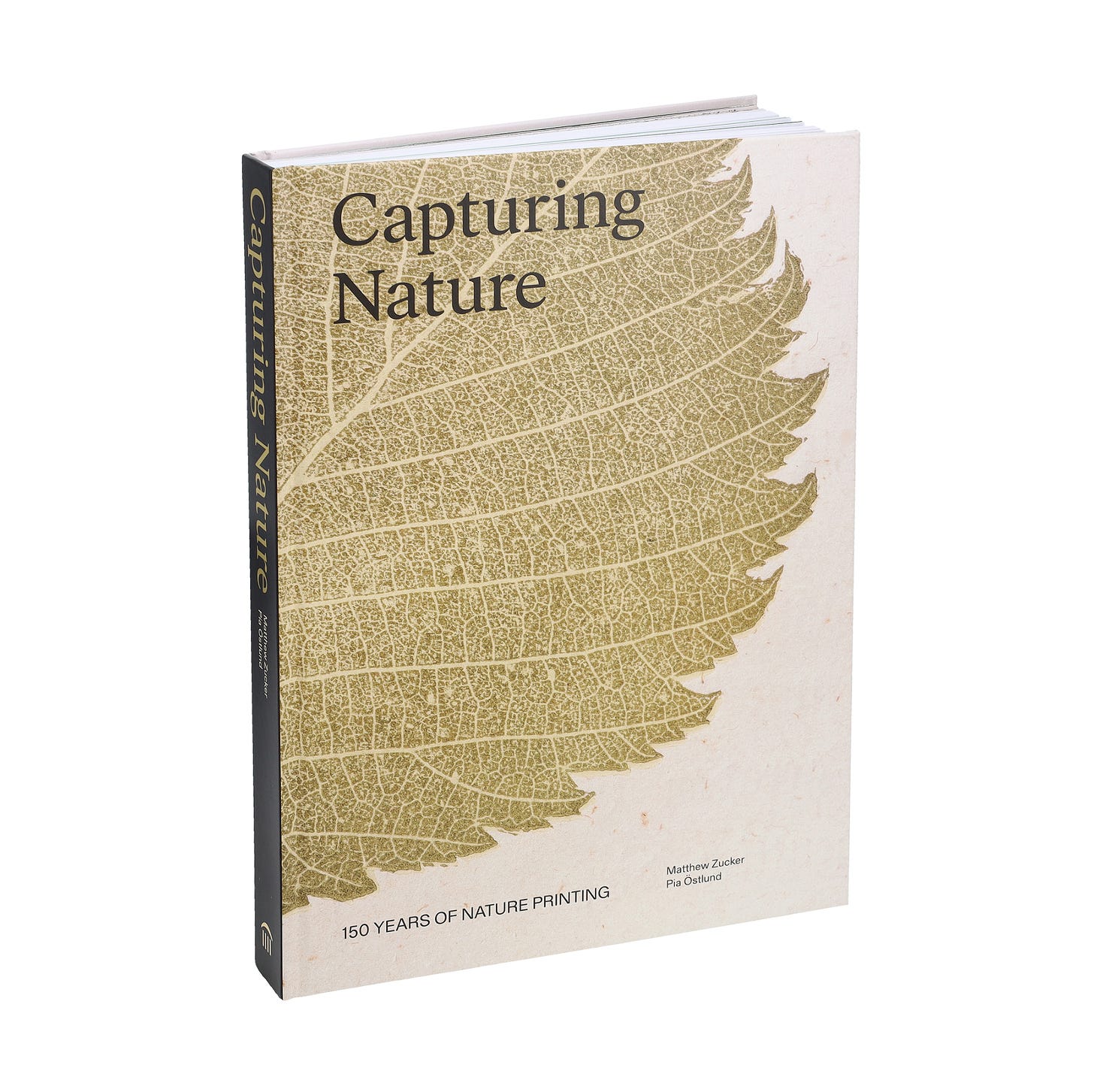

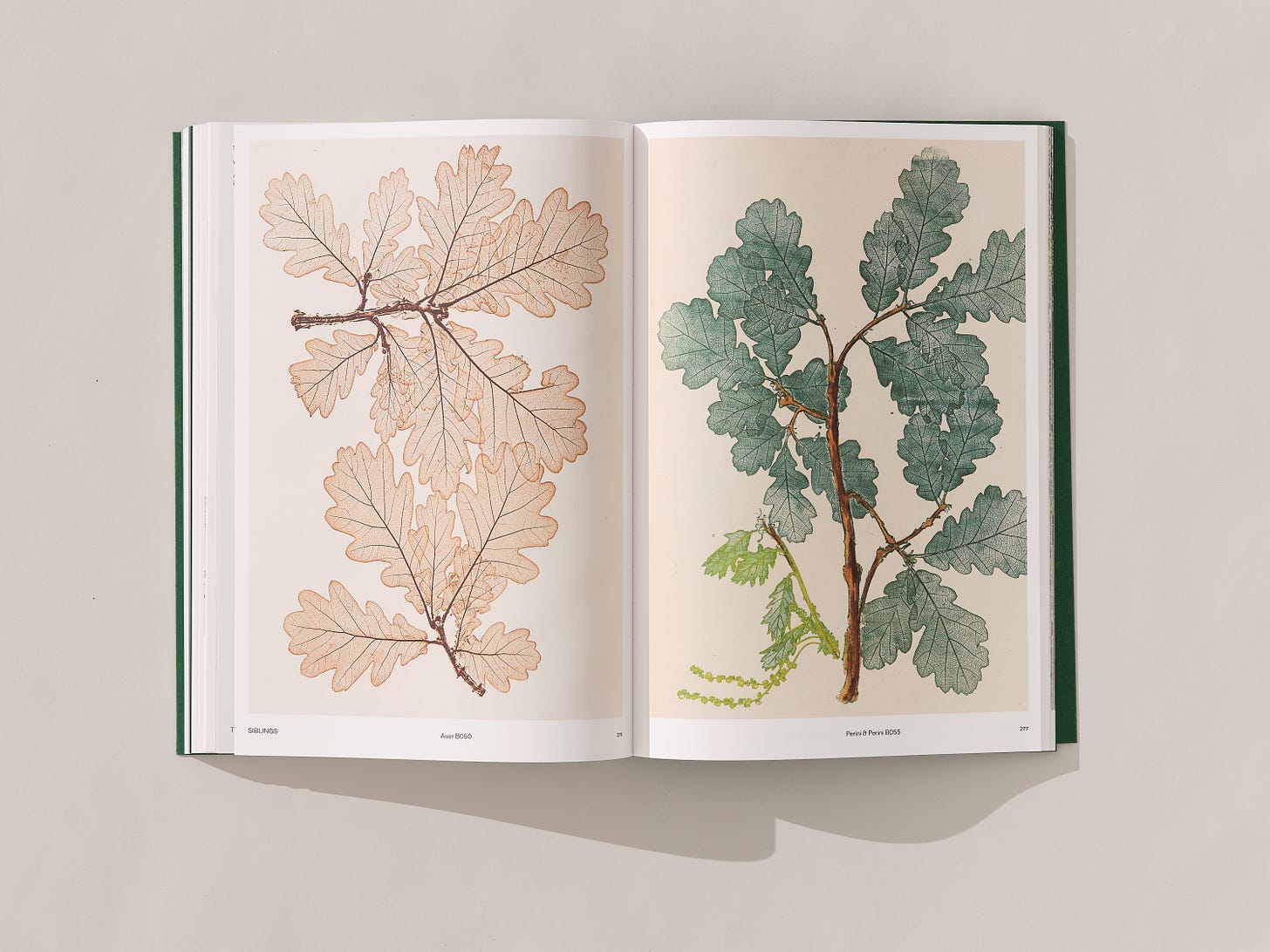

Last fall I came across the book Capturing Nature at my local library, sitting on the shelf of new arrivals. The gift of an unknown book landed in just the right hands.

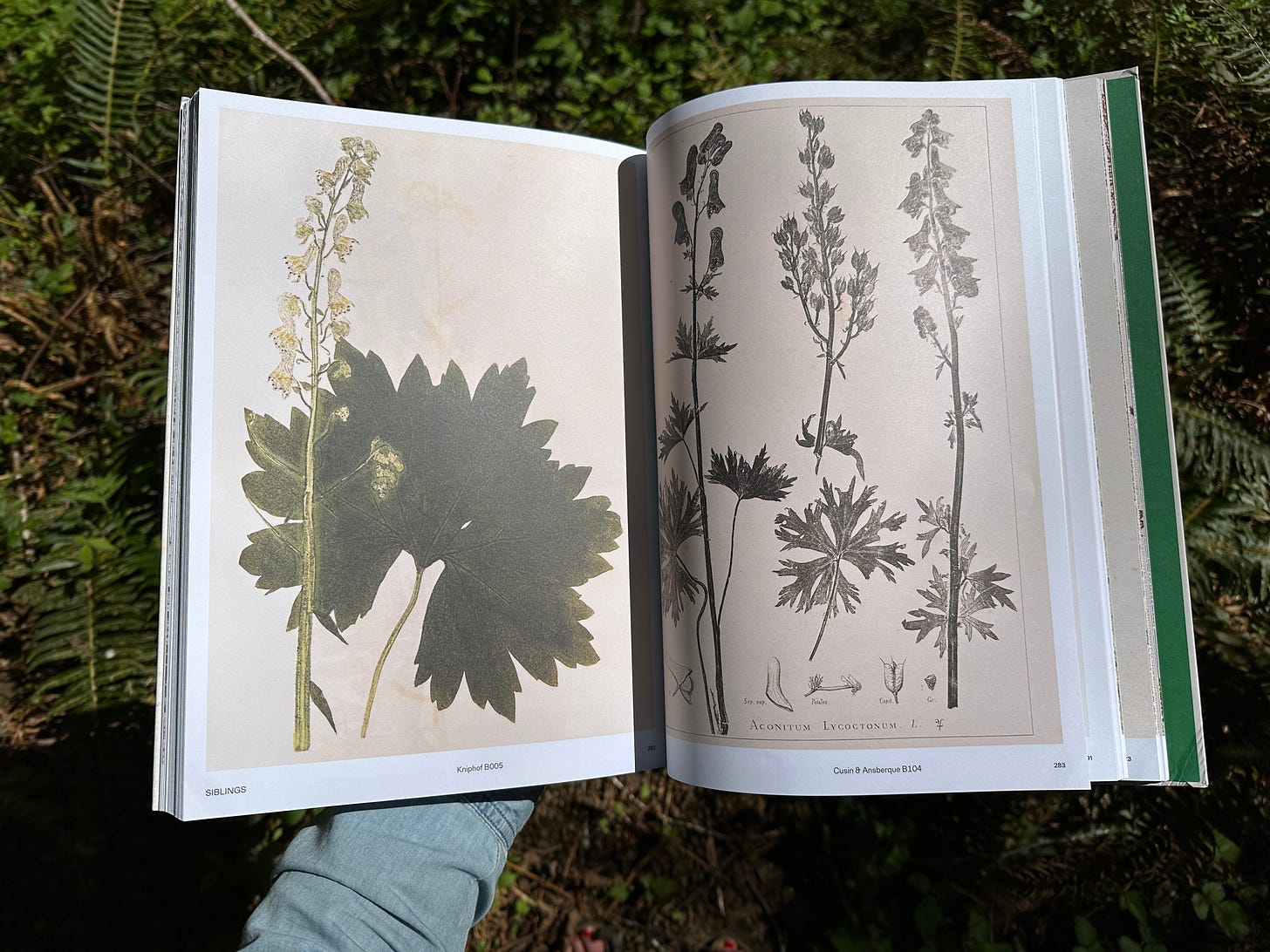

Nature plays a prominent role in my own work, and I have a particular affinity for botanical illustration (which I wrote about last year), so flipping through the pages of this book felt incredibly captivating. Like discovering the natural world in a new way. I’ve also worked on enough papercuts of organic forms to know how difficult it is to really capture what a branch, or a leaf, or a fern, really looks and feels like. Which is what makes nature printing so fascinating: it involves actual organic matter as its base medium.

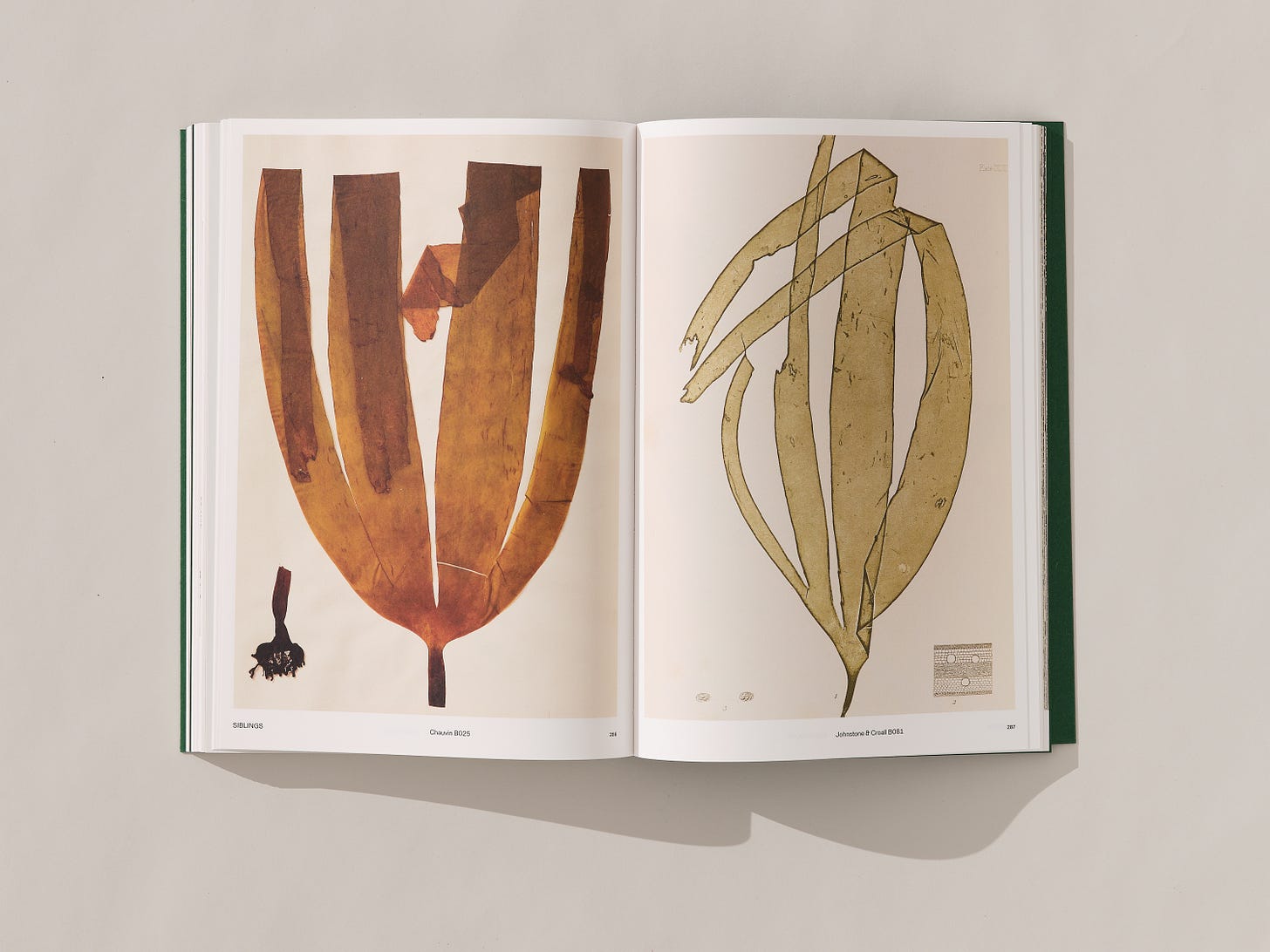

The book is based on the Zucker Collection, the most extensive collection of nature prints ever assembled, with more than 13,000 images across 130 rare and seminal works from 1733 to 1902. There are all kinds of things printed in here: ferns, seaweed, snakeskin, even rocks. Even in just the first few pages of the book, you can tell that putting it together was an enormous endeavor. Artist and co-author Pia Östlund has such an interesting story about she came to this world—it all started with a book of ferns—and helped to revive the art of nature printing.

I’m excited to share this interview with her, and hope that is spurs your own investigations into the world around you.

-Anna

Anna Brones: How did you get started on this nature printing journey?

Pia Östlund: I'm Swedish but I've lived in London since 1997. I moved here to study at Central Saint Martin’s College of Art & Design and I did graphic design, but I always loved printmaking. Somehow my projects always involved nature. After I graduated, I started working freelance. I ended up working for all these different botanic gardens doing visual identity and signage that explains the different plant collections.

One place I became very involved with is Chelsea Physic Garden, the oldest botanic in London which was founded in 1673 and set up for early doctors to study plants as medicine. The Garden has a small reference library of rare books, some of which date back to the 16th century. As we went looking for images to use to illustrate different publications for the garden, I became more and more familiarized with this library.

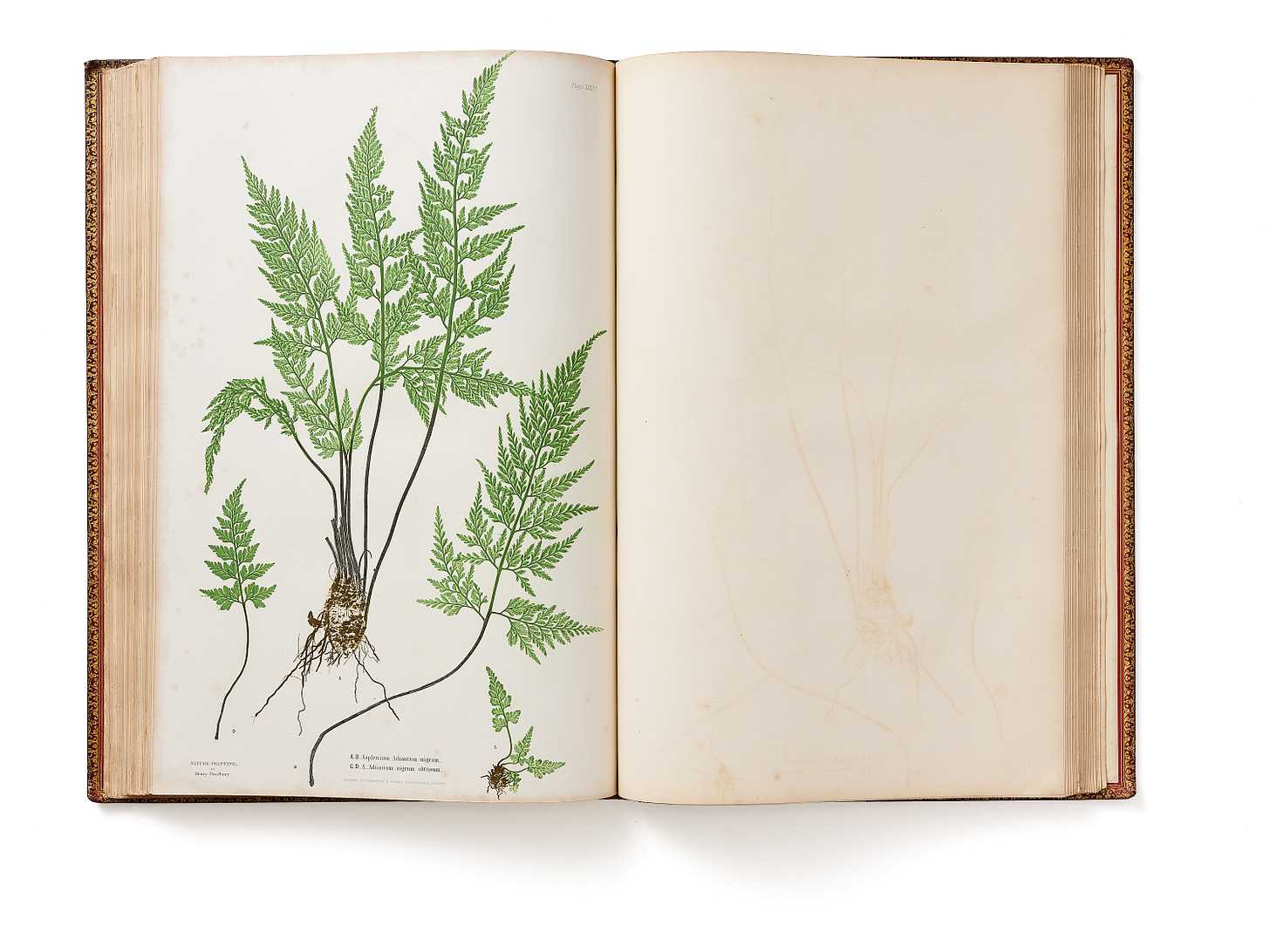

Rosie Atkin, the Curator at the time said, “have you seen this book of ferns?” She brought out this really large book, which depicted all the ferns of Britain and Ireland. The prints were so strange, I didn't know at all what I was looking at. The images were life size, highly detailed and looked too real to be drawn. They clearly weren’t photograph. You could feel this 3D kind of texture if you ran your hand over them.

All it said at the bottom was “nature printed” by someone called Henry Bradbury. And I was like, “what is this?” Then I had the idea that it would be so amazing to be able to send a printing plate through a press and find a print like this at the other end. That was in 2010 or 2011, and I’m still on this mad quest.

When something is creative, you feel it. It's like you wake up.

-Pia Östlund

At the time, I started to google “nature printing” to see if I could find a course on how to make these prints but quite quickly realized that no one was working with this technique. Something I did find was the reference to a patent description of nature printing from 1853. I managed to track down a copy of this at St Bride’s Library, a really brilliant reference library devoted to printing and located near Fleet Street, which is London’s old printing quarters.

At St Bride’s they not only had a copy of the original patent but they also had further samples of nature printing. Although I understood very little of what the patent described, I felt compelled to decipher it and try to put it to practice. There was something about nature printing which brought together lots of different interests of mine, you know, printing, nature, books, a bit of science, and history of art—a skeleton to hold all the different things that I wanted to look into. Then I told as many people as I could that I had found this lost printmaking method and had decided to revive it, so I had no way out!

Since I hadn’t seen an original nature printing plate, I didn't know exactly what I was trying to achieve. The patent description sets out that you start with a sheet of lead and a dried pressed plant, like an herbarium specimen. You place the plant onto the lead and exert enormous pressure onto it. Afterwards, when you then peel off the plant, it will have left behind the most detailed impression in the lead. But you can't print from the lead because it is too soft and it will also tarnish and react with the inks.

In the 1850s, they had just invented the battery and the process they called electrotyping, which is similar to electroplating. You use an electric current to deposit a very fine layer of metal. In the case of nature printing, you have your original—the lead plate—which gets inserted into an electrolytic bath which includes dissolved copper sulphates. The copper sulphates become attracted to the surface of the lead, and particle by particle it starts to build up a thin layer. After let's say 20 hours in this bath you can peel this fine copper layer off the lead plate and find that it is a perfect mirror positive of the original lead impression.

When I began, I had zero knowledge of printing history. I had tried many different types of printing at college, techniques such as lithography, engraving, screen printing, but I didn't know anything about printing presses, metal work or anything like that. What made it more difficult was that there was only one known surviving printing plate, and it was in the collection of Harvard University and I didn't have the money to go. Instead I was following up on all different kinds of leads.

Eventually, Eric Hochberg, a distinguished botanist in California and a founding member of the Nature Printing Society told me that he might have seen some printing plates in a library in Vienna many years earlier. He couldn’t remember which library, but it was an exciting lead! I emailed all librarians all over Vienna, until one of them came back to me and said, “we have something, I don't know what it is. It's not in our catalogue, but you can come and have a look at it if you want.”

Before long I was on my way to Vienna and what the helpful librarian had been referring to turned out to be not just one, but over two hundred original nature printing plates! They had just been sitting on a shelf in a back room since the library (which used to be located next door to the original Vienna printing office) had bought the plates for their value in copper about a hundred years earlier.

Another helpful avenue came via the Printing Historical Society, which I had first heard of via St. Brides. As I was struggling to find the right printing press it was suggested to me that maybe I could use the printing facilities at University of Reading for a week during the summer. I ended up staying for two years and enrolling in a Masters program there. Finally I could pull all the different aspects of my research together. But as you can see in our book, Capturing Nature, there are so many variations on the nature printing method, so it's been kind of trial and error.

AB: How did you connect with Matthew Zucker [co-author of Capturing Nature]? Did he have a family collection of nature prints?

PÖ: Matthew is an art book dealer with a keen interested in nature. His grandfather founded Zucker Art Books and Matthew learnt from him. One of Matthew’s first finds were a series of albums with pressed seaweed. Soon after, at an auction in London, a big collection of nature printed works came up for sale and he just felt the attraction. Gradually, over a period of fifteen to twenty years, he built up a huge collection.

I love that nature is just doing its own thing. It's so complex, we'll never really grasp it.

-Pia Östlund

AB: How did you go about making a book out of this huge collection?

PÖ: This was during the pandemic lockdown. It was a difficult task because that collection is huge (around 130 different works, many with several volumes and something like 15000 images in total) and with the travel ban and all public institutions and libraries closed. Luckily, I had saved a lot of photocopies from my earlier research. Matthew kept sending me snapshots on WhatsApp. Maybe half of the works I knew and half of them were new to me.

We ended up working for about three months solid until suddenly restrictions lifted and the collection ended up in London. This meant I could do the final research from the actual items and we could have selected plates photographed – another huge task. It was so much work. It was crazy. I think I will probably never write anything again. [Laughs]

AB: It's probably one of those projects that if somebody had told you how much work it would be, you wouldn't have said yes. Your book fits in with a general popularity and interest in scientific, botanical illustrations and prints, as well as history. Why do you think this is having a moment?

PÖ: I’m not sure. A lot of these prints are from the late 1700s and 1800s. That's when the arts and the sciences began going separate ways. The Industrial Revolution eventually brought us to this point in time where we have a climate crisis and people dream of going back to nature. Perhaps it makes sense to go back to where it all started to fork out.

There's also a renewed interest in craftsmanship. I think what's wonderful with all these different books and prints is appreciating the wide range of impressions and types of mark and different qualities of paper. Whereas digital can make everything look the same. And maybe people also want to have a go at making these things.

AB: Anna Atkins is in this book, and I do feel that cyanotypes are like that for people. Especially for people who feel like they want to engage in a creative activity, but they feel like they have a lot of hang ups about art because they feel they can't draw—in a cyanotype you get to be creative in a composition or in what you choose to print. I think the pressure is kind of off for you creating something beautiful as the individual artist, because you get to let nature do that. Looking at these prints, I keep thinking that nature is the artist and the printmaker is the conduit for getting it onto the page.

PÖ: Yeah, when it was invented that was the way it was promoted, as a truthful representation. I've run a lot of workshops, mainly monoprinting from natural objects and people can quite quickly get a good result. It really makes you look and notice nature, and then you can take it in whichever direction of your interest.

AB: Do you feel like you look at nature in a different way after working on this project?

PÖ: Sometimes I have nightmares about plants and printing. [Laughs] I'm definitely much more focused, on leaf shapes, the shapes in nature. And now, seaweed, which I haven't really looked into much before. When you look into the water, you see them just as green, brown or red entangled things around your feet. But when you float them onto a sheet of paper and dry and press them, it's so amazing the intricate pattern and shapes.

I always loved nature and wanted to make something from it. Besides the challenge of trying to recreate this method I also liked the idea of having this very exact way of making images, whilst being able to keep my drawings looser.

AB: That makes sense, because you have one medium that allows you to get that precision. One question that I have been thinking about, is that we think of creativity as a very human trait. Working with nature in this way, do you see nature as creative?

PÖ: I just feel that all the solutions are there. I like to think of nature as a force, regardless of us. Having worked with so many botanic gardens, you look through these old books where it starts with people going out traveling, and they start collecting. The illustrations in early books of collecting places plants next to a dead bird, next to a coin, next to a feather from a headgear. We look at these images today and they don't seem like a scientific grouping. And then botanists developed the idea that specific plants were related to each other and could be divided into families. There are constant attempts to organize nature, but at the same time, I love that nature is just doing its own thing. It's so complex, we'll never really grasp it. Whichever criteria for ways to group we come up with, it's an impossible pursuit because this only lasts until that system is deemed inadequate and another one is invented. We will never fully grasp it, and that’s what makes you want to learn more all the time.

AB: What does it mean to be an artist?

PÖ: I think to me the idea of being an artist is having the freedom to not have to fit what you do into a specific bracket. It makes sense to you, it doesn’t have to be accurate from any scientific point of view.

AB: What does it mean to be creative?

PÖ: It’s the thing that makes life make sense.

When something feels creative, when you feel completely in tune with what you're doing, when you get into a sort of flow—that's what I love. With printing in particular, because you have something actively that you're trying to place but then you also constantly are like, “is this right? Does this make sense?”

It's kind of nerve wracking and totally exhilarating at the same time. When something is creative, you feel it. It's like you wake up.

Thank you Pia!

Check out more Creative Fuel interviews here.

Resource links

A gorgeous Limited Edition of Capturing Nature

The Capturing Nature website with lots of photos and information about nature printing

Explore all of Pia’s work here.

Upcoming Creative Fuel Workshops + Events

Our next Creative Fuel Studio Session is May 23rd. This is basically like a creative happy hour/hangout to connect with creative community. Bring a project to work on, or just show up! More info + sign up.

Next Create+Engage workshop is June 12, 2024, 5-6:30pm PT. We’ll be announcing speakers soon, but you can register now and get it on your calendar. Full schedule is here. All of this programming is free, made possible by paid subscribers and other supporters. Thank you!

Do you enjoy Creative Fuel? You can support this work by becoming a paid subscriber. You can also order something in my shop, attend one of my workshops or retreats, or buy one of my books. Or simply share this newsletter with a friend!

So interesting and inspiring, diving into research. This makes me think of all the inventions and techniques through history that has already been forgotten or discarded. So happy that this idea is in a new and available book now!

What a beautiful book!!