Embracing Imperfection

Taking creative lessons from nature and the work of Anna Atkins to remind us that perfectionism is a trap

Creative Fuel is a newsletter about the intersection of creativity and everyday life. Prompts are focused on helping us tap into our creative process, no matter our medium, and are often more about questions than specific projects. For Women’s History Month I’m taking inspiration from women artists, and in this one, general subscribers get the intro section, and paid subscribers get the full prompt. Paid subscribers also have full access to the archive of prompts.

Perfectionism is an ongoing conversation in my household and in my sphere of friends. Since we live in a capitalist, productivity-driven society, I’m going to go ahead and guess that perfectionism plays a role in your world as well.

I had a few moments of messing up this past week, so telling myself, “you made a mistake, learn and move forward,” instead of, “you’re doing a real shit job here lady” required real practice. It always does. Good to have this reminder on the wall.

Let’s call it “perfectionism and its discontents.” We know perfectionism usually doesn’t serve us, but damn, it is difficult to extract ourselves from its demands.

“Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people… Perfectionism is a mean, frozen form of idealism, while messes are the artist’s true friend. What people somehow (inadvertently, I’m sure) forgot to mention when we were children was that we need to make messes in order to find out who we are and why we are here — and, by extension, what we’re supposed to be writing.”

-Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

WHAT EVEN IS “PERFECT”?

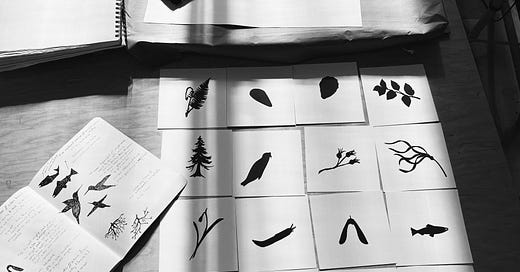

I’ve recently been working on creating a series of silhouettes based off natural organisms found in the Pacific Northwest, and I’ve been thinking about how difficult it is to get a silhouette to look like how the organism looks in nature. A flattened, 2-d version with clean lines? That’s doable. But the real subject? It’s always more complex than that.

The edges of a leaf are always rougher than you might automatically draw them. Look close enough and the edges of the sword fern are spikier than you think. Madrone has way more branches than your eye can focus on. A salal leaf has been half eaten away, leaving it looking nothing like in the guidebook. Lichen?! Enough said.

The resulting papercut silhouettes often look too clean, too perfect. They’re not organic enough.

For creative inspiration, I like looking at botanical illustrations. In fact creatively documenting plants was a pathway for women to participate in a world of science when few were allowed in.

These scientific renderings are meant to hone in on the intricate and precise details of the natural world, help us to better understand. You would be hard-pressed to call it abstract art. And yet…

These illustrations are human interpretations of plants. The artist depicts them in a way that you would probably never see in real life. There’s nothing in the background, no other plants in the way to obstruct your view. They are detached and removed from their natural habitat, held in the space created by the paper or canvas.

In order to depict specific details and elements that might be hard to capture through other means, botanical illustration abides by scientific standards. But it’s still a creative interpretation of the world around us.

"There is an aspect of creating a representation of a ‘perfect’ subject for the purpose of understanding, which is important for grasping how things may differ from that baseline standard,” scientific illustrator Skye Young told me (she’s teaching a virtual science illustration workshop this month). “You would never know what's ‘wrong’ with a plant, or how an environment has impacted a plant, if you didn't know what it was ‘supposed’ to look like in the first place.”

Notice all these air quotes we’re employing. What is “perfect”? What is “wrong”? What is anything “supposed” to look like?

I like how Leonard Koren frames this in Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers: “... when does something's destiny finally come to fruition? Is the plant complete when it flowers? When it goes to seed? When the seeds sprout? When everything turns into compost?”

If we’re hung up on perfection we have no room to grow or change, no space for the cyclical nature that’s part of being human.

I think that, just like with color, how we see and understand the world is as much about what we’re looking at as how we’re perceiving it and what aspects we’re paying attention to. That’s where art and science can intersect—through deep investigation we can revel in the complexities, go beyond our own assumptions, acknowledge that there is no “perfection.”

As Lulu Miller writes in Why Fish Don’t Exist: “The work of good science is to try to peer beyond the ‘convenient’ lines we draw over nature. To peer beyond intuition, where something wilder lives. To know that in every organism at which you gaze, there is complexity you will never comprehend.”

Perhaps our pursuit of “perfection” is more about identifying a goal or structure that feels convenient and understandable, rather than digging into those wilder, unknown complexities that make up our realities.

INSPIRED BY NATURE

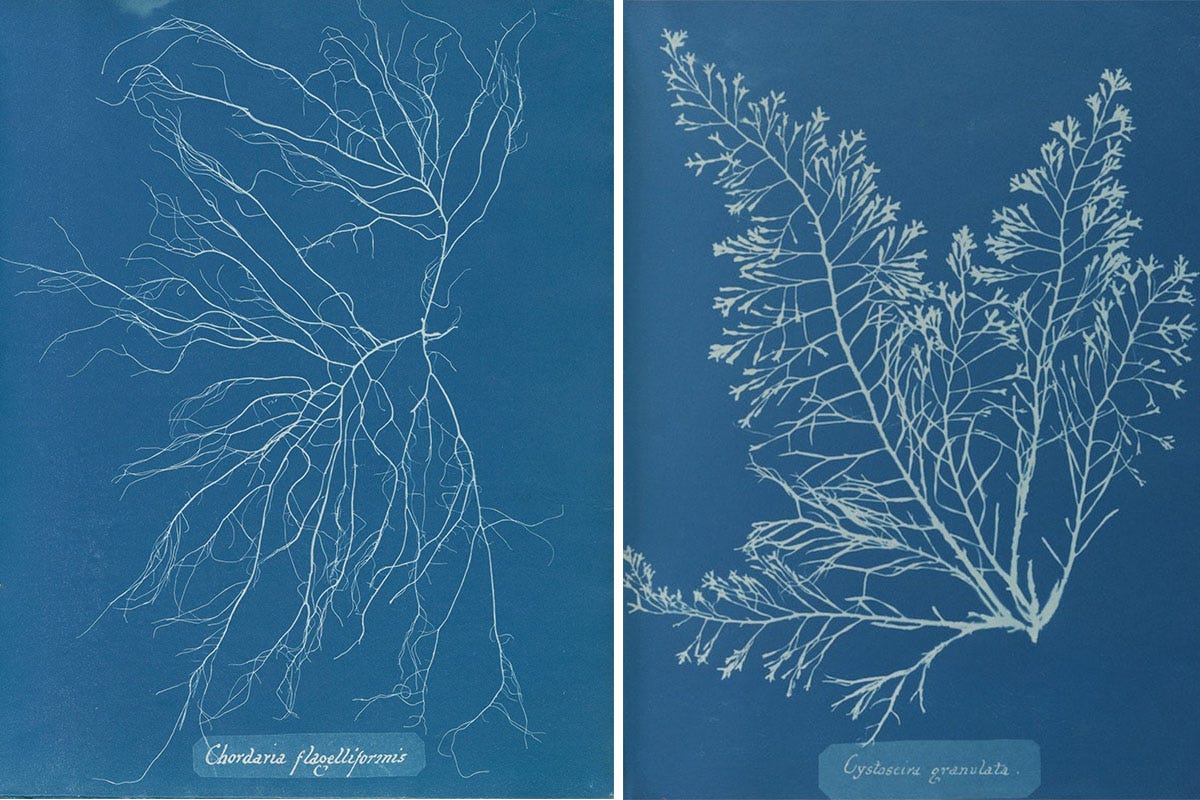

I’m particularly drawn to the work of Anna Atkins (1799-1871), a trained botanist and the author of the first book to be entirely illustrated with photographs. She loved the natural world and was a skilled illustrator (hello shells). But it was the photographic cyanotype process—in which light-sensitive paper is exposed to the sun, turning it blue—that allowed her to truly explore the natural world.

In 1843, she wrote to a friend describing her book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. She explained why she opted for the photo printing process, noting that in her subject of choice, many “are so minute that accurate drawings of them are very difficult to make.”

Working with this method allowed Atkins to explore nature in a way that illustration didn’t, and her prints are works of both science and art. The cyanotype process is still used today—I am always inspired by the work of Brooke Sauer and Hannah Perrine Mode. Those blues!!

I’m drawn to Atkins’ work because in her quest for scientific accuracy and exploration, she managed to capture the plants in their truest nature. This isn’t a perfect and idealized rendering, it’s a documentation of the intricacies and nuances that define natural organisms. If we didn’t know any better, what we might have otherwise deemed “imperfect.”

As Stephen Hawking once famously said, “One of the basic rules of the universe is that nothing is perfect. Perfection simply doesn't exist. Without imperfection, neither you nor I would exist.”