Writing (and Reading) Letters

The analog art of letter writing.

Cards that are good for sending notes to friends // As part of my book research, I’m looking for some input from fellow cold lovers

Hello friends,

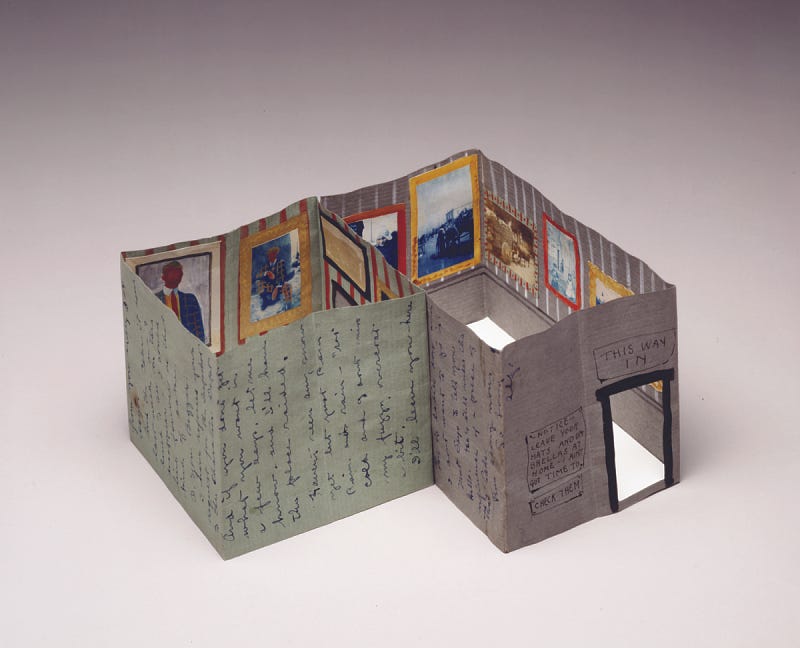

On Friday January 10th in 1913, Alfred Frueh, a cartoonist and caricaturist for The New Yorker, sent his fiancee a special letter. She was heading off to Paris, and he wanted to be sure that she could train for the “gallery marathon” that awaited her in the French capital.

This wasn’t just any letter—it was a letter that also turned into a tiny pop-up art gallery, complete with minuscule works of art.

I love this so much. The creativity, the intention, the fact that there is a sign at the entrance that says, “leave your hats and umbrellas at home — I ain’t got time to check them.”

Many letters were written in my younger days. Sent across oceans and continents. I used to have a box filled with them—messages of love and friendship that outlined past versions of myself. The box disappeared in a move, and the habit has dwindled over time. But I’m slowly working at trying to revive it.

There’s something about pulling a letter from its envelope, the anticipation in what words will be held on the page. In many ways, I think it matters less what’s actually written—the act of writing the letter, of receiving it in the mail is enough.

Writing letters was once such an art that entire books were devoted to how to do them properly. In How to Write Letters, a book from 1876, J. Willis Westlake offers up a detailed exploration of the ins and outs of letter writing. For Westlake, the importance of letter writing was threefold: business, social, and intellectual.

He described letter writing as a “social obligation.”

We are naturally social beings; and pleasure, interest, and duty equally demand that our friendships and other social ties should be maintained and strengthened. In many cases this can be done only by means of letters. No one would willingly lose out of his life the joy of receiving letters from absent friends, nor withhold from others the same exquisite pleasure.

These days, most of us probably write very few letters, but our desire for correspondence and connection remain the same. We may have moved that desire into group chats and text threads, but there is joy in communicating what we’ve seen, what’s inspired us, and what we’re thinking about.

But that kind of digital communication feels easier, more seamless. Letter writing takes more time, and every time I sit down to write a letter, I always feel the pressure that it must be good, must be robust, must be worthy of putting in an envelope and sending out into the world. Must, must, must, should, should, should. Pipe down inner voice!

Those thoughts get in the way, keep you from actually putting the letter in the mail. Better to write something short, stick it in the envelope, and move on with your day.

Westlake too had thoughts on quality over quantity.

Take pains; write as plainly and neatly as possible — rapidly if you can, slowly if you must. Good writing affects us sympathetically, giving us a higher appreciation both of what is written and of the person who wrote it. Don’t say, I haven’t time to be so particular. Take time; or else write fewer letters and shorter ones. A neat well-worded letter of one page once a month is better than a slovenly scrawl of four pages once a week. In fact, bad letters are like store bills: the fewer and the shorter they are, the better pleased is the recipient.

Letters do not need to be overdone, overthought. The most honest and truest of words is what matters. In The Art of Letter-Writing published in 1762, letter writers are cautioned about making their letters too grandiose.

Write as you speak; that is, without Art, without Study, and without making a Show of your Wit.

There’s beauty in the researched and the well versed, but the point here is that a letter doesn’t have to suffer from those constraints. That it’s personal, raw, human. No need for polish.

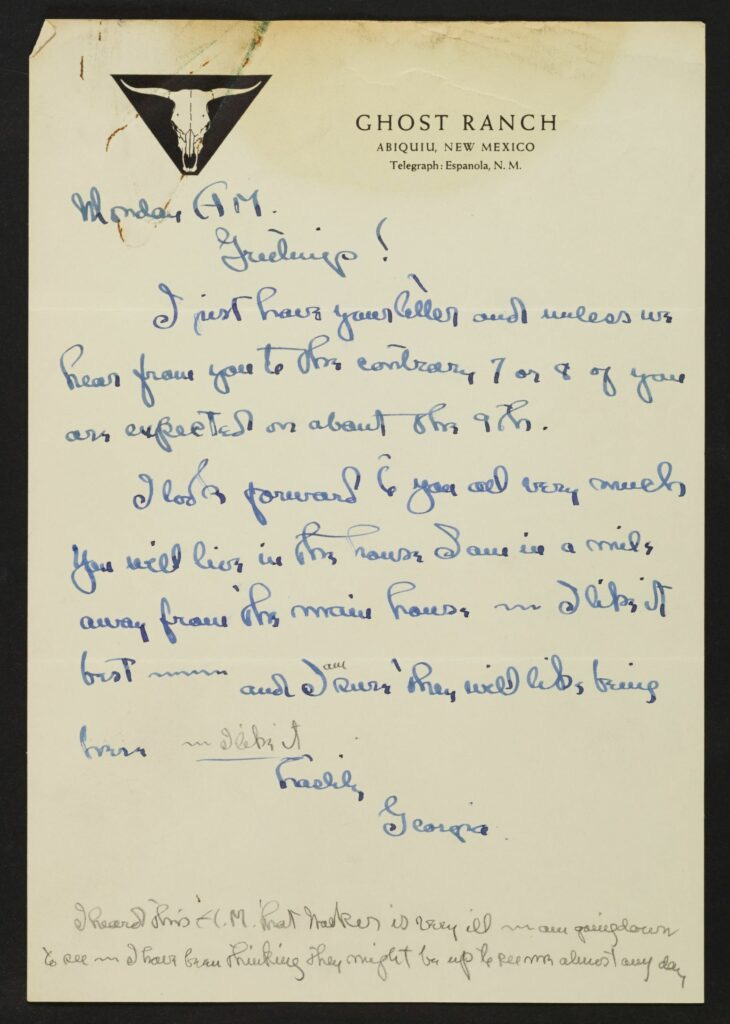

We’re drawn to letters and correspondences from the past, and not just for the excellent letterhead design (looking at you Georgia O’Keeffe).

What pulls us into old letters is not the grandiose revelations, it’s the declarations of the most human emotions—love, sadness, joy, grief—and the routines and simple observations that make up an everyday life.

Letters can be so intimate, and I always wonder if the people whose letters are compiled posthumously would enjoy knowing that their words are available for mass consumption. Would people have written their letters in the same way if they know they would have been seen?

Letters from Tove is a book I enjoy coming to again and again, a view into a personal world that isn’t my own but that makes me feel like Tove Jansson is a close friend. But her letters weren’t meant for me. Would she care that I enjoy reading them?

I think of my own craving for keeping what is sent to me. “There will be no retrospective,” is an ongoing line I have to repeat whenever I am trying to clean up my studio and putting things in the recycling bin is. A writer friend once told me that when she receives a letter she reads it and promptly puts it in the recycling bin. Read and release!

But when they’re kept, when they become logged in the archives of the creative past, these personal exchanges can often become the source of inspiration.

Kurt Vonnegut’s letter to high school students immediately comes to mind. A high school English teacher had encouraged her students to write letters to famous authors and invite them to come visit the school. Vonnegut couldn’t come, but he wrote thanking them for the invitation, and offered up this gem of wisdom:

Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what's inside you, to make your soul grow.

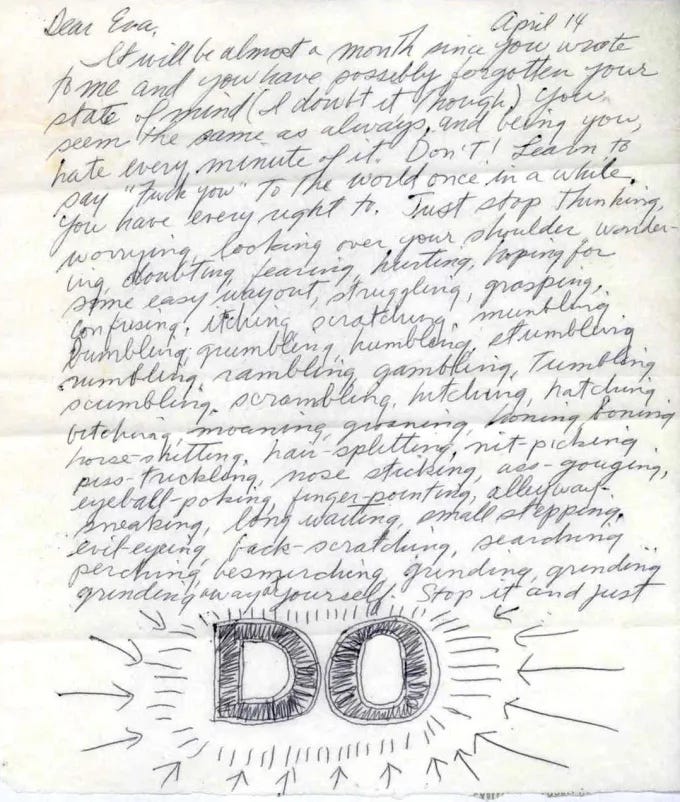

And then of course there’s Sol LeWitt’s famed letter to Eva Hesse1.

Dear Eva,

It will be almost a month since you wrote to me and you have possibly forgotten your state of mind (I doubt it though). You seem the same as always, and being you, hate every minute of it. Don’t! Learn to say “Fuck You” to the world once in a while. You have every right to. Just stop thinking, worrying, looking over your shoulder, wondering, doubting, fearing, hurting, hoping for some easy way out, struggling, grasping, confusing, itching, scratching, mumbling, bumbling, grumbling, humbling, stumbling, numbling, rambling, gambling, tumbling, scumbling, scrambling, hitching, hatching, bitching, moaning, groaning, honing, boning, horse-shitting, hair-splitting, nit-picking, piss-trickling, nose sticking, ass-gouging, eyeball-poking, finger-pointing, alleyway-sneaking, long waiting, small stepping, evil-eyeing, back-scratching, searching, perching, besmirching, grinding, grinding, grinding away at yourself. Stop it and just

DO

That’s the version that gets shared around a lot, but the full letter was a bit longer, and I appreciate this section:

…when you work or before your work you have to empty your mind and concentrate on what you are doing. After you do something it is done and that’s that. After a while you can see some are better than others but also you can see what direction you are going. I’m sure you know all that. You also must know that you don’t have to justify your work — not even to yourself.

In writing today’s newsletter installment, I came across a lot of “how to write a letter” posts. You know, the things with bullet lists of specific instructions. Including details on what stamps to get, what paper to buy, who you should write a letter to, and ideas for what you should write about.

I guess it’s the modern version of books devoted to the topic, but it annoys me nonetheless. I regularly lament to friends that we’ve turned some of our most basic human ways of creative expression into Methods. Yes, capital M.

We seek instructions on how to do something perfectly instead of just starting, we want tips and tricks so we can do it “right.” Worse: we even get tempted by shortcuts. There are apps now for handwritten cards, AI robots happy to make a note or letter look like you wrote it. If I was going to write a letter on how I feel about that, it would be a letter of a mess of angry scribbles.

I get it, we’re all pressed for time, just trying to figure out how to stay afloat and keep our lives moving forward. I know I don’t take the time to sit down at my desk regularly and pen letters, even thought I want to be that person.

But are we willing to give up on the activities that keep us creatively engaged and connected? Are we willing to outsource these things that bring us joy, make us move our hands, provide us a moment of respite from the screen and the demands of digital life?

You don’t need me to tell you how you should write a letter, or how to buy a stamp, or what paper to use.

The only advice we need was written on a page several decades ago.

Stop it and just

DO.

-Anna

Goodnight Moon stamps are coming this year!

The ultimate postcard: people posed with books.

I was thrilled to come across Finn Hopson’s work, getting into the sea in order to take pictures of starling murmurations. Seriously, just looking at these will make you feel better about things.

More illustrated letters from assorted artists.

Lindsay Stripling wrote this week about losing her dog, it’s a beautiful essay on art and grief.

Creative Fuel is 100% reader supported.

You can support this work by becoming a paid subscriber.

You can also order something in my shop or buy one of my books. Or simply share this newsletter with a friend.

Worth watching Benedict Cumberbatch doing a reading of this letter.

As a subgenre it's hard to beat postcards! I once spent a summer transcribing old ones at Yellowstone. Just a scrawled line or two on most. No time on a postcard to be precious. Yet plenty of time to be outlandish. They're the punk song of letter writing.

When my Nana passed away my mom found all the cards and letters I sent to her when I was in college and the years after when I lived a few hours away. I was never super far during those times and called and came home often, but I guess I always wanted Nana to know in multiple ways the important space she held in my life. Even after we moved back home I would stop by and leave notes and some handpicked flowers or some cookies when I knew she was out shopping with my mom. That she kept the notes and that I got to know she did is a gift that roots me in the love I always felt from being her granddaughter.