"Art is real and money is fake"

A conversation with printmaker Nicole Manganelli of Radical Emprints about the Anti-Capitalist Love Notes series, the labor of art, and what it means to be a working artist.

Creative Fuel is a newsletter about the intersection of creativity and everyday life. Today’s newsletter is part of a series of ongoing interviews with different artists and creatives.

This newsletter is entirely reader-supported and paid subscribers help bring it to life. If you enjoy reading it, please consider supporting. You can also come to a weekly Creative Fuel Wednesday session or join me for a workshop (I’m teaching a virtual one this Saturday).

About a month ago in a writing workshop, one of the fellow attendees showed up on Zoom wearing a black “you are worth so much more than your productivity” t-shirt.

“I have that sticker right here!” I exclaimed, holding up the small circular sticker that I keep as a reminder to myself on my desk.

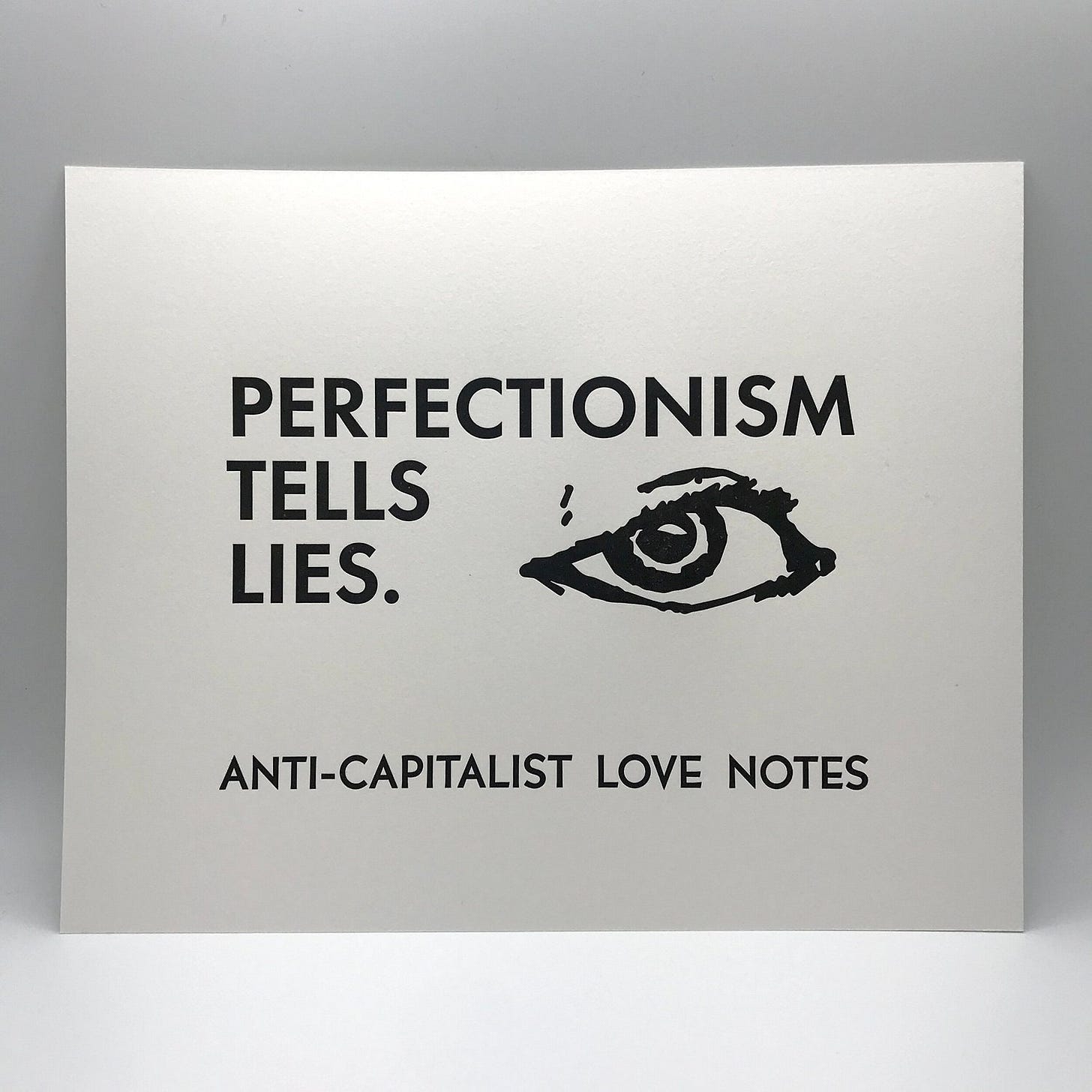

That t-shirt and sticker are a part of the Radical Emprints series of Anti-Capitalist Love Notes, created by Nicole Manganelli. Printmaking has a long history with political activism, and Nicole’s work embodies that political history and energy. A printmaker, poet, and graphic designer, Nicole also co-facilitates grassroots fundraising trainings for movement organizations with the Resource Organizing Project.

I am drawn to Nicole’s work because she finds a creative, poetic, and artful way to tap into some of the darkness and woes that we can all feel functioning within our current economic system.

I’ve never wanted to be the producer of tips and tricks for running an art business, which means that publicly I’ve often veered away from talking too much in detail about the intersection of art and money. But it is a space that I spend my work existence in.

Inevitably, this intersection of art and money—and all the ups and downs that come with it—is a conversation that comes up a lot within my circle of friends and creative collaborators. If you’re a working artist, writer, or any other form of creative work that doesn’t fit the usual mold of “JOB,” then it’s something you’re often navigating, and some days are better than others.

I do think that talking openly about money, identifying the stories we tell ourselves about it, and analyzing the worth that we and society attach to it (or “unf*cking our worth” as the excellent book title says) is an important part of building a sustainable path as a working artist. We might enjoy making our art, we might come to it out of a love for the medium and a desire for the practice, but art is work, and art is labor.

Like with anything that’s a complex and nuanced subject, I find it helpful to talk to and learn from other people about how they navigate this space. I am always inspired to find artists who do so in a way that cultivates a committed, powerful creative practice in the process. Nicole is one of those people, and I connected with her for today’s interview.

This is a conversation about money and what it means to be a working artist, but it’s also a challenge to rethink how we approach our work to infuse it with the things we believe in. It’s about art as a vehicle for change. As I was putting the finishing touches on this interview yesterday, I got a Patreon update from some of my favorite artists The Far Woods. In it, Nina Montenegro shared this quote:

“We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.” - Ursula K. Le Guin

Le Guin’s words are from her acceptance speech in 2014 for the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. All to say: we need change, we need the imagination for different realities, we need art.

With that, let’s dive into the art and power of words with Nicole.

Anna: Can you tell me a little bit about your path of how you became a working artist? Have you always been a printmaker?

Nicole: The work I’ve done for the majority of my life has been several forms of violence prevention/intervention, and/or social justice-focused culture change work. When I was 19 I started volunteering at a shelter and hotline supporting people experiencing relationship violence, and then I became an educator and advocate at a rape crisis center in western Massachusetts.

I started facilitating workshops during that time and fell in love with facilitation as a tool for deep understanding. For a bunch of years I facilitated workshops and trainings with young people and adults in mostly public schools, primarily about preventing and responding to homophobia, racism, ableism, classism, xenophobia, transphobia—work that other folks might call “bullying prevention,” but that I think should always be named instead by the oppression it is rooted in.

In 2013 I started learning about grassroots organizing through the Southern Maine Workers’ Center, and was deeply involved in the workers' center, primarily as a grassroots fundraiser and grantwriter, for about eight years.

In 2012, I took a one-day letterpress printing class from David Wolfe—a talented and generous letterpress printer with many years of experience—and I immediately fell hard for the process. As a lifelong poet & lover of words, it was the intentionality of hand-setting type that really filled my heart. In those first couple of years, David helped me make a broadside that said, “Every word is either a tiny triumph or a lost opportunity.” That’s kind of an intense way to live life, but if I’m honest, it’s still part of my orientation to writing, as a poet and printmaker.

My path to being a working artist has involved doing a lot of other things for money and slowly building a creative practice. I’ve been lucky enough to have some wonderful mentors during this process, including Pilar Nadal (the director of Pickwick Independent Press, where I’ve been a member since 2015-ish) and LK Weiss, the founder & creative director of Portland Design Co, where I’ve been doing graphic design work (in addition to my freelance work) since 2018. I wanted to move into graphic design in order to hone my skills for printmaking, and also to get out of the nonprofit grind that I’d been in since 2001.

I met with LK in 2017 to ask for her advice, and one of the things she suggested was that I give myself projects in order to learn design software and to build my skills. So… I gave myself the project of digitally designing a 78-card tarot deck using only letters from the typeface Garamond to make all of the images, and the Printers’ Tarot was born! Clearly I took her advice seriously, because that project took me about a year to complete, and I learned so much in the process.

What does it mean to you to be a working artist? How do you find a balance for creative work that sustains you and inspires you and creative work that pays the bills?

Being a working artist (which for me means earning a portion of my income from printmaking) is a total dream—I'm so very grateful to be making things that people resonate with and feel fortified by, so much that they want my prints in their spaces. But being a working artist is also filled with contradictions and uncertainty and self-doubt—sometimes all at the same time!

Holding several types of work at once helps. I've managed to find a combination of paid work that gives me steady enough income (for the most part) that I can actually dedicate time each week to being at the printshop. But for a lot of artists, that's just not possible.

We need to do a much better job (understatement of the millennium) of eating the rich and redistributing their wealth, including to artists—and primarily to artists who have been systematically silenced or excluded from opportunities that make it possible to access paid time for creating, like BIPOC artists, queer and trans artists, artists who are parents or who have disabilities or who are poor and working class.

There are so many barriers to accessing arts funding, residencies, paid art gigs... when folks are in positions to create access to these opportunities, we/they need to be thinking about every step in those processes, and figuring out how to remove the obstacles for folks whose art we desperately need in this burning world.

Along those lines, you refer to yourself as an "art worker.” Can you talk a little bit more about that and what it means for you?

Sure! I talk about myself as an art worker because I think that under a capitalist economic system, we are defined by our relationship to work—if, how, why, why not, when, where we exchange our labor for money. Of course we should be able to define ourselves by so many other factors—including the ways we are in relationship to each other and the planet—but in an economic system that is built on exploitation and extraction, our relationship to work often becomes our singular definition.

In addition, sometimes folks don’t see art-making or creative work as actual labor, which makes it easier to invisibilize that work and exploit individual artists. So that’s some of why I include it in my list of descriptors about myself.

I also believe that neoliberalism has hyper-individualized our forms of work in order to break our collective power as workers. The “gig economy” is another way of saying the “economy in which individual workers can be systematically isolated, indoctrinated to believe that their worth is inherently tied to their productivity, and then taught to compete with each other over scraps instead of demanding an entirely different system.” But since that’s kind of a mouthful, I guess “gig economy” will have to do.

What draws you to printmaking and letterpress?

I started learning letterpress printing during a time in my life that I started calling “the beautiful precipice,” where my understanding of the world and my politics were shifting quickly, which felt both liberating and exciting and also deeply scary. I read The Revolution Will Not Be Funded during that time and started to dig into anti-capitalist study and reading & learning about organizing and power-building.

Letterpress printing was a way to slow down long enough to figure out my developing political lines—literally thinking through concepts and ideas and statements letter by letter, word by word, and then printing and sharing them. I also quickly fell in love with the democratic possibilities of printmaking. I heard Josh MacPhee speak last fall, and he said something about how often in the art world, value is defined by scarcity—a singular artistic object has value because it is one of a kind or only a few. But in the movement art world, the value we can derive from our work is from making prints widely available, carried by many folks in the streets or during an action or in other public spaces.

So, yes, I want to make beautiful prints, even prints that might be considered “fine art” by some people, but my primary goal is for them to function in the streets and in people’s homes and workplaces and public spaces as ways to nourish organizers of all kinds with fierce, beautiful words that keep them invested in movement work for the long haul. And if they also end up in a gallery, hey, great! But that’s not my primary goal.

Can you talk about the process behind bringing a print to life? How do you go from concept to tangible printed piece?

I keep what I was just going to call a journal, but I actually think it’s just a poetry notebook—I write down phrases and concepts and ideas and sometimes full poems that I then sit with to decide if and how I want to print them. I also keep ideas in the notes app on my phone, and often go back to them to edit and refine over time. And then, sometimes the ideas just come—while I’m in the printshop, while I’m sitting in front of a type case, while I’m grieving or raging about each new calamity unfolding around us.

Sometimes it’s the type that is the inspiration—the “queer as in madly in love with the burning world” print that I did originally as a riso print, I ended up making a letterpress printed version because I found the most beautiful Q and O that were stray sorts (individual letters) in Pickwick’s collection. I immediately knew what I wanted to use them for. I still can’t keep that print in stock, incredibly. It sells out every time. What a gift.

How did the idea for your Anti-capitalist Love Notes series come about? What was the first one?

I went to a training with the Catalyst Project in 2013, and one of the facilitators said something about how we are worth more than our productivity. It was the first time I’d heard that sentiment, and as a person who has struggled with chronic depression and anxiety, the relief I felt was overwhelming. It felt like a sweet, deeply anti-capitalist love note. That’s when the idea was born, and then when I cobbled together my first tiny tabletop press later in 2013 (using parts from an incomplete press I was gifted and the body of a press I bought from a sweet New Yorker named Henry whose dad had been a printer well into his 90s), the “worth so much more than your productivity” love note was one of the first things I made.

Here’s a note from my tiny poetry book at the time—where I wrote down the typeface I printed it in—and forgot the n in Bernhard.

Let’s talk about art and money: how do you view the intersection of the two?

Um… art is real and money is fake? And also, given our current circumstances of global imperialist capitalism, both are necessary for (most people’s) survival. The intersection of art and money is full of the contradictions that we all live with on the daily, and as an anti-capitalist artist, I think a lot about how to be principled in my work and in the process of selling my art, and also how to acknowledge and honor that I also have rent and bills to pay. People should be able to access art for free or low-cost, and also, artists should be paid a living wage for their work. I give away a lot of art, and have also been running my Solidarity Art Fund since 2020, which allows me to give away art and still get paid.

On the landing page for that fund you write, "We need bread, but we need roses, too." What does that mean for you?

It’s a reference to one of the major slogans of the 1912 Massachusetts textile workers strike1, as a way of saying that our lives should not just be about meeting our basic needs, but that we also deserve to experience beauty. When I use it in reference to my Solidarity Art Fund, I mean that people should be able to access art not only when they have “disposable income,” but because they are human and art is also a critical form of nourishment and sustenance.

What does it mean to be an artist?

I think each artist defines that for themselves. For me, it means noticing the world and reflecting it (or refracting it) back to other people in ways that resonate or inspire or move folks to dream and build new worlds and to take action toward collective liberation.

Ok, one final question: what does it mean to be creative?

I think my answer to this might be the same as for what it means to me to be an artist, except in an even more expansive way. I think creativity is about thinking beyond the bounds of typical problem-solving or visioning—it’s using your imagination to build unexpected expressions of beauty in unlikely places.

You can support Nicole’s work by buying a print or card in the Radical Emprints Shop, or donating to the Solidarity Art Fund. A percentage of paid subscriptions this month will be donated to the fund as well!

RESOURCES + INSPIRATION

Here are some of Nicole’s recommendations:

Reading

Reading the work of incredible thinkers & writers & revolutionaries like June Jordan, Grace Lee Boggs, and Anne Braden has been deeply inspiring—and truly life-changing–for me. Also writers Franny Choi, Raechel Anne Jolie, Andrea Gibson, Jenny Odell, and Dane Kuttler (a very very abridged list!) are all folks I’ve been reading in the last couple of years and whose work I feel very grateful for.

Artists

In terms of contemporaries—basically all of the artists of Justseeds, including folks like Favianna Rodriguez, Josh MacPhee, Roger Peet, Andrea Narno. Folks like V Adams, Oscar at Tender-Heart Press, Kathryn at Blackbird Letterpress, John Fitzgerald at Fitz Press, my comrades Pilar Nadal & Rachel Kobasa at Pickwick Independent Press and on and on…

SUPPORT

Creative Fuel is a reader supported publication. If you enjoyed reading this and want to help bring it to life, please consider subscribing. Paid subscribers help to make this work possible and you get access to all the weekly creative prompts (which are sent out on weekends).

Love receiving art in the mail? You can also sign up for one of my 2023 CSA (Community Supported Art) Shares.

https://substack.com/profile/34772500-nuk/note/c-16352497?utm_source=notes-share-action