“We are neither the cancer of the Earth nor its cure. We are its progeny, its poetry, and its mirror.”

A conversation with Ferris Jabr about his new book Becoming Earth, the precision and poetry of science writing, and the power of gardens.

Creative Fuel is brought to life by paid subscribers. If you like getting this newsletter the best way to support it is to become a paid subscriber. You help to keep the coffee flowing! And you help support the Create+Engage series + you can catch up on all the 2024 workshops during the month of August.

How do we think about the planet that we call home? A place that we inhabit or a place that we are a part of?

For much of human history, the Earth has been seen as alive, a place that lives, breathes, and evolves. We too are a part of that process, not just beings that exist on the planet, but beings that are part of the planet, an extension of that planet. That’s the premise behind Ferris Jabr’s new book Becoming Earth, which takes a look at the fascinating science behind Earth’s systems and inhabitants, and how planet Earth has co-evolved with all of the organisms that call it home.

As Jabr writes:

“Life gives our planet an anatomy and physiology—breath, pulse, and metabolism. Without the transformations wrought by life over billions of years, Earth would be utterly unrecognizable. Life does not merely exist on Earth—life is Earth. We have as much reason to regard our planet as a living entity as we do ourselves—a truth no longer substantiated by intuition alone, nor by one man’s vision, but by a preponderance of scientific evidence.”

As someone who did not end up going down a scientific path during my academic years, I find myself continually drawn to exploring the complexities of the world around us. Unfortunately, we live in a time when we have largely separated the arts and the sciences. Pursue one path and you’re told you can’t do the other. Much like thinking about the planet requires a larger, more interconnected approach, I believe that the arts and sciences deserve the same. After all, for so long they were closely tied together.

It’s why I am excited about anything that manages to weave the two together. Jabr’s book does exactly that, bringing an eye for poetry and beauty to the technical and precise world of Earth science. His words help to illuminate the awe and wonder that can be found under our feet and above our heads.

For a taste, here is how Jabr describes a venture into Klamath National Forest:

“Moss pillowed every rock, trunk, amd stump. Wisps of pale lichen hung along the length of every branch, as though the trees were antique chandeliers caked in melted wax. Persistent fog and a light, intermittent rain evoked the atmosphere of a cloud forest. The stout smell of wet earth and rotting leaves flavored the air, muddled with their near opposites: the scent of woodsmoke and ask.”

In my mind, the ability to understand complex scientific systems and be able to beautifully communicate them is a superpower, and beyond wanting to celebrate this book I wanted to learn more about Jabr’s process behind the work that he does.

I hope that you enjoy our conversation. Grab a cup of coffee and settle in!

-Anna

Anna Brones: The initial seed for this book came about a decade ago when you learned how rain and the rainforest interact in the Amazon. Do you remember exactly when you learned about it?

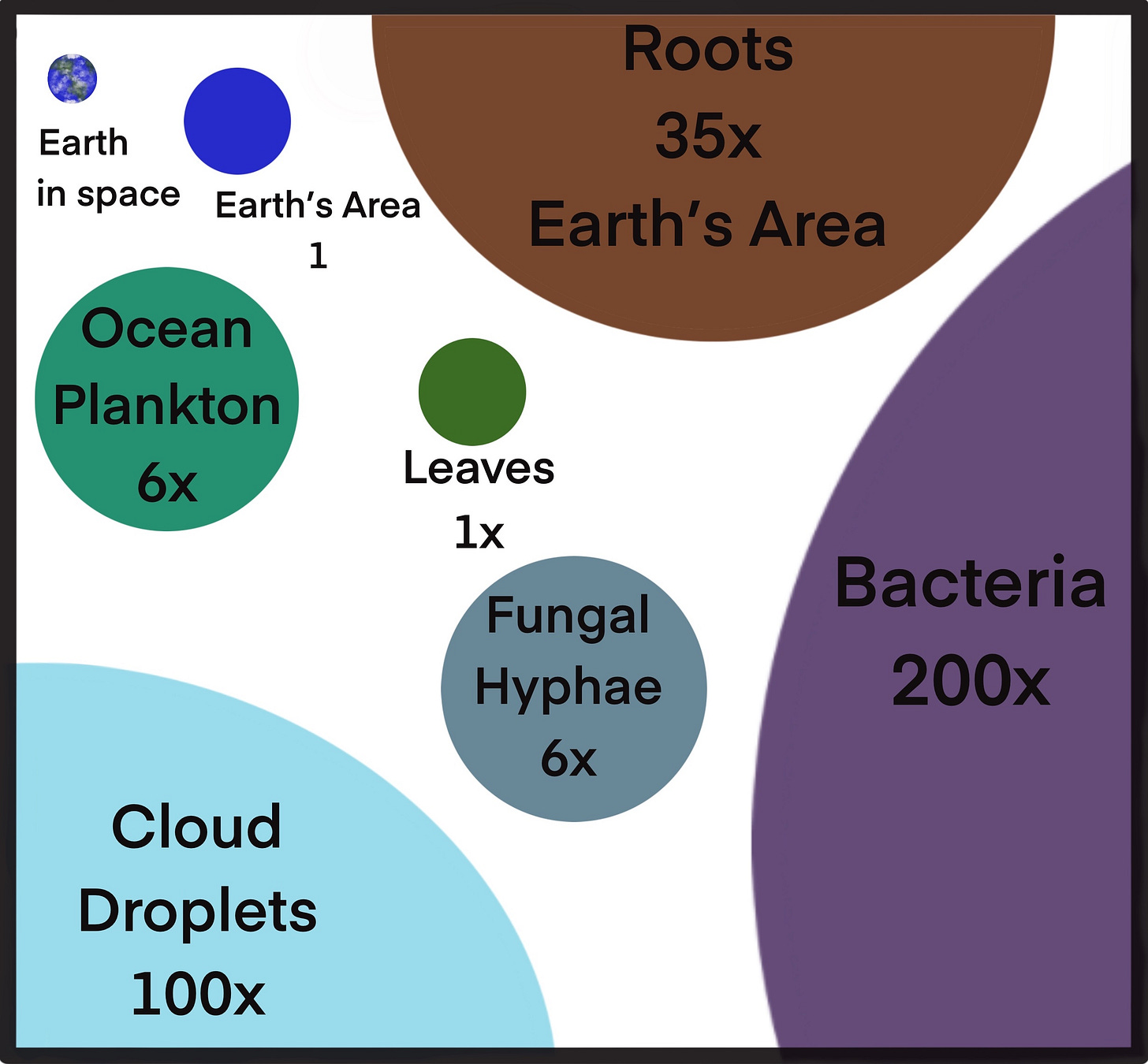

Ferris Jabr: I was in grad school at New York University and I was learning a lot about the world of plant behavior, communication, and intelligence. I was really fascinated with the idea that plants have a lot more agency in their environments than we often give them credit for. Part of that ongoing research was learning about the Amazon, so I probably first read about it in a research paper. It has been understood for centuries that trees and plants are involved in the water cycle, in the sense that they're performing transpiration. They're pulling water from the soil and what they are not using is getting pulled out of them into the sky. But this new research revealed that transpiration was just one part of the whole story.

Trees and plants were also releasing these incredible plumes of tiny biological particles. It gets even more complicated: they're releasing these invisible gases, salts and organic compounds. All of this biological matter was rising into the atmosphere with the water, and together, was creating the ideal conditions for rain clouds to form. It wasn't just plants anymore. Now it’s the spores of fungi and little bits and pieces of insect shells that were getting up there, and little flakes of animal fur. Basically, all the life in the forest was involved in accelerating the water cycle. That was really exciting to me. It felt like somebody had sprinkled pixie dust all over the typical textbook picture of the water cycle that we all learned in elementary school. It was just so much more wondrous and magical than I'd ever realized.

I was also thinking about those visuals we have from elementary school: the water cycle, the carbon cycle, and just Earth systems in general. How would you re-envision those visuals to portray some of that awe and wonder?

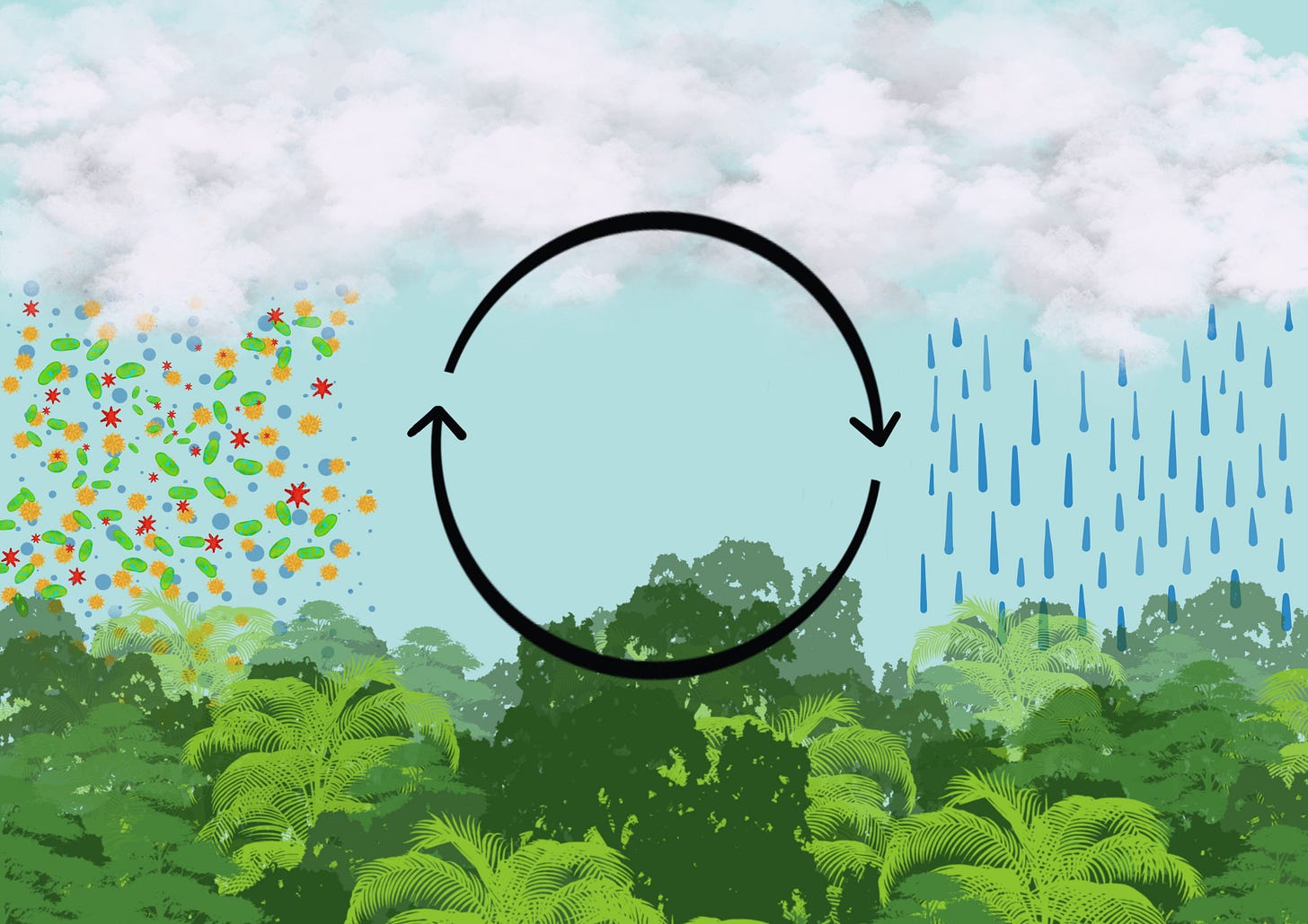

I've actually been teaching myself very simple iPad art, using the app Procreate. I've been giving various talks about this, and to illustrate this point, I made a little illustration where on one side I have the rain pouring down from the sky, and on the other side, I have all of the biological matter and water vapor rising up from the forest.

For me, those are the two most important sides of that equation: to visually represent that the rain is not just being passively received by the forest, at least half of it is being generated by the forest. All this biological matter that is thrown up into the sky is accelerating cloud formation, seeding ice crystals in the clouds, and doing all this amazing stuff. Scientists have actually collected these bioaerosols, these tiny biological particles, above the Amazon rainforest, and then taken these beautiful photos of them through extremely powerful microscopes.

You know how pollen grains are so beautiful up close, right? They look like these incredible sculptures. They have their own architecture.

To that point, you use a few examples in the book that combine art and science. One is from the gate that René Blinet designed for the 1900 Paris Exposition and you also mentioned Kelly Jazvac, the artist who had worked with Charles Moore, the researcher on plastic pollution. What are your thoughts on the importance of the role of art and science together?

From a really young age, I was fascinated by nature and science on one side, and reading, writing, arts and humanities on the other. I've never really been able to let go of those dual interests. The fusion of them is often the most powerful, clarifying, and compelling way to explore any idea you're interested in.

What I love so much about science writing itself is that it has a lot in common with science as a process. It’s all about precision, accuracy and rigor. But it’s also literature, which is an art form. It's a craft, it's a creative process. Trying to bring together logic and lyric, precision and poetry, is what I'm always going for in my writing. I guess that's partly why I was drawn to art over and over again in the book.

I think sometimes artists, philosophers, and creative people hit upon certain insights sooner than science comes to those same intuitions and insights. That’s understandable because science is all about very slowly accumulating a huge amount of evidence. It takes a long time to do that, repeating the same thing over and over again to see if it holds. Whereas intuition and insight can operate much more rapidly. But it’s also because science is often very resistant to anything that it considers “unscientific.” Anything that's too close to religion, mysticism, or just pure intuition or mythology is often rejected or rebuffed by mainstream scientists because they don't want to sully the perceived objectivity of science.

I think a lot of the book is grappling with this, coming full circle back to these ancient ideas that have been percolating for a very long time. Now Western science is affirming those ideas for itself. We don’t need science to confirm these ideas within Indigenous mythologies—they exist in their own right. But Western science is coming to similar ideas on its own terms right now. That fusion of ancient thinking, ancient mythology and then modern contemporary science is a really appealing and compelling way to look at things.

Many of my intellectual heroes are very much straddling the artistic and the scientific. I became obsessed with Emily Dickinson a few years ago, and I read her entire poetry collection. I wrote down every single time that she mentioned any kind of living organism, and I was fascinated by the fact that the majority of her poems were inspired by everyday creatures. She was an extremely avid gardener and she kept a very meticulous herbarium where she would collect wild plants and press them and label them. Her father gave her a greenhouse so that she could garden year round even in the winters of the East Coast. It was clear that science, nature, ecology, and botany were very much cross-pollinating her poetry. She loved to borrow the language and terminology of science and find new ways to use it within her poetry. She was very much immersed in both of those worlds at the same time, and I really relate to that.

I think I love botanical illustrations for that reason. There were so many women of a certain era who weren't allowed to do science, but they were able to come at it through art. It’s interesting to think about who gets to hold and pursue knowledge. Science has to be slow and methodical, but we also need the imagination and thinking far beyond what we can conceive and conceptualize. As I was reading the first chapter of the book, I was thinking that on one hand, this idea that the Earth is alive feels really revolutionary. But at the same time, it’s very intuitive. Can you talk a little bit about that, and even how you thought about that?

Yeah, absolutely. The basic idea of the world being alive is incredibly ancient. We see this manifested in cultures, mythologies, and religions going back way, way back in time, before records even began. Then we see it persist in the early stages of Western science. People like the ancient Greeks, Leonardo da Vinci, James Hutton. Alexander von Humboldt were comfortable speaking of the planet being alive, of nature as a whole being, a living entity.

With the rise of reductionism and the modern scientific method, and imperialism and conquest, that idea was no longer sanctioned in the halls of science. Now the animate was very separate from the inanimate, segregating them into categories, rather than seeing them as a continuum. It has taken a long time to come back to that idea of continuity. I think we're now seeing the beginnings of a movement that's going to bring a lot of these ideas to the forefront of our collective thinking.

I know of a lot of books in the works that are exploring similar ideas. Robert Macfarlane has a book coming out next year called Is a River Alive?, that explores animacy and legal personhood, rights for nature, recognizing that these ideas are simultaneously ancient, and yet, as you're saying, they also feel novel and revolutionary. That’s for a lot of reasons. They’ve been so harshly ridiculed and criticized by Western science, so there's a lot of stigma attached to them. There’s something bold and refreshing about declaring them anew now.

There’s a huge amount of new scientific evidence to support aspects of these ideas. That’s part of what I'm trying to do with the book—to provide a scientific girding for these really ancient ideas that were unfairly dismissed. These ideas are taking on new relevance and urgency because of what is happening right now to the planet, and our role in what we have done to the planet.

There's no way any reasonable person could deny the power of life to transform the planet, because we are such an extreme example of that. We're the latest chapter in this really long coevolutionary saga of all forms of life continually transforming the planet over billions of years. We've inherited all of these changes. For the most part, these changes have been great for the habitability of the planet—they've really made the planet more complex, more biodiverse. Then we come in and do very much the opposite.

That simultaneous antiquity and modernity of these ideas—I find it really exciting and enthralling. I think a lot of people, like you're saying, they hear this and think, “Yeah, that feels right.” But they also feel like they were told “No, you're not allowed to believe that. You're not allowed to declare that as a scientific truth. That's a personal belief or a religious belief, not a scientific statement.” I think that's starting to shift.

So many of the greatest revelations in the history of science, they do feel very obvious after they've become accepted. Like, “How did we not see that? How did we not understand that?” I think this is very much a piece of that.

That makes me wonder if there is a link between when we started separating those worlds and when we started separating art and science. With art, you have this real sense of deep wonder, imagination, and curiosity, you’re able to go in very wide directions, which is essential for scientific discovery too.

Science has had so many other names in the past. There are contexts in which science and art are basically interchangeable: it’s a craft, a technique, a way of doing something. Historically they've become more and more segregated, but originally they were almost the same.

Even the scientific method can be applied to the creative process and creative approaches to problem solving. I think we've done a real disservice to ourselves by parsing them out to two individual things. I was curious about this for your process. You said earlier that you aim to combine this element of precision and poetry. Can you talk a little bit about what that process looks like? How do you hold that precision of poetry at the same time?

For me, it always begins with intensive research, that's the bulk of the work: reading a huge number of research papers, consulting textbooks, doing interviews with experts, and compiling really extensive detailed notes on all this material. Sometimes it feels like building up a well or a dam and the water has to get to a certain level before I can do something with it.

I love mapmaking metaphors, too: I feel like it's very much surveying an intellectual landscape and I need to have a solid enough understanding of this wider landscape before I can blaze the particular path through it.

It begins with that period of deep exploration and research, and then it's about a kind of translation. How do I take this scientific, technical, jargony material and make it lucid and understandable to a typical reader? Once I've done that, once I understand how to explain something, how do I take it to the next level where it becomes poetry?

Ideally, I'm not just stating something clearly or summarizing something clearly—I'm writing it beautifully. The composition itself is now something to admire beyond just its clarity or accessibility. That’s where flow states and reveries come into play. I do sometimes enter these kind of trances where I'm trying to put myself into a state of mind where I'm enthralled and inspired by everything that I've learned about nature. I'm trying to make the prose emulate and match my inner experience of wonder.

There are other times where it gets a bit more technical, sentence by sentence. Maybe the way I'm stating it right now feels like I read this before: how can I rearrange things? How can I say this in a different way so that it’s more original and memorable? That’s where I get so much inspiration from fiction and poetry, because fiction writers and poets are so good at finding word combinations that are unexpected and that stick with you. Like when Emily Dickinson talks about volcanoes as “phlegmatic mountains.” Probably nobody in the history of English language ever put those two words together in that way and I've never seen anybody do that since. That sticks with you.

Science writing can also be like that: a can of gasoline is not just a can of gasoline, it's actually 20 elephants’ worth of ancient life. That is a scientifically true statement. It sounds absurd, but it's true! That's the material truth of what gasoline is.

I'm a brick by brick writer. I lay down one sentence, get it right, then I move on to the next sentence. I find it very difficult to write if I don't have a beginning that I'm happy with. For me, it’s all about rhythm and flow. I can hear when I'm striking the wrong notes. Like when you're playing the piano and you hit a wrong note—it's grating. I hear that in my writing. I have to stop and fix it and then I can move on.

Do you write any fiction or poetry, or have any other creative mediums to help facilitate more of that flow state?

Fiction was my first love. I've written fiction since I was young, and I've continued to do so, but I've never attempted as an adult to actually publish much fiction or poetry. It's something I'd like to try more seriously.

Most of the nonfiction I read is for work and learning the craft of nonfiction. In the evenings, when I'm turning to something for pleasure, it's almost always fiction. Lately, it's a lot of audio books. I like the feeling of somebody telling me a story in the evenings, especially after having read so much on screens and paper during the day.

It’s challenging to be a professional creative. I often long for the combination of the intense inner creative fire I had in my youth, plus the relative lack of responsibility. It’s a very freeing combination.

-Ferris Jabr

Do you do any visual art?

I have tried to teach myself a little bit of watercolor. One of my dreams is to write and illustrate something, like some sort of nature or wildlife book. And I've been doing a little bit of iPad art, which I find really freeing because you can attempt to recreate almost any style or medium on this one device.

There’s the app Procreate, I just love it. You can make your own brushes. I took a picture of one of my favorite flowers: a snake's head fritillary. It has this incredible snakeskin-like, checkered pattern on its petals. It was one of Emily Dickinson's favorites, and it was one of Vita Sackville West’s favorite flowers. She was one of Virginia Woolf lovers and she has this amazing description of it1.

I took a photo of it and I put that into Procreate and then I made a brush that mimics the texture of that flower. Now I can add that to text or anything I want. I just love the versatility and flexibility of that digital medium, which I hadn't really explored before.

I also love the fluidity of watercolor, and I like ink and watercolor sketches where you outline something in ink and you just add touches of watercolor here and there. You allow the water itself to act upon the paper. It gives a very organic feeling to illustrations.

I want to talk about your garden, because I think that's also a real creative expression. Reading your book, I was thinking of Robin Wall Kimmerer and Braiding Sweetgrass, and this idea of having a reciprocal relationship where we tend to and engage with nature. How has that experience been in your garden? Has it changed how you think about how humans interact and tend to the earth around them and the reciprocal relationship that we have with it?

Absolutely. The garden became the most direct and personal way in which I was engaging with a lot of this material in the book. I loved gardening from a young age but didn't have much opportunity to do it seriously until a few years ago when my partner and I bought this house. I think of the garden as a living canvas or living sculpture. That doesn't fully capture it, because it is so reciprocal and dynamic.

So much of the work is performed by the plants and their symbiotic partners. Once we give them the time, the opportunity, and the space, they really get to work on their own. I do see me and my partner, and humans more broadly, as kind of co-stewards. I would never call us “managers” of the Earth system or “rulers” or “controllers,” but I do think that many forms of life do act in a sort of stewarding capacity, whether they are consciously doing that or not.

We can look at the incredible symbiosis of grazers and grasslands, and how they maintain each other. It's not like the grazers have all the power, or the grasses have all the power. There’s a reciprocity there and a mutual dependency. We very much experienced that in the garden. Where we're pushing things in this or that direction, and it's pushing back against us—we're trying to find some sort of, mutually beneficial, dynamic equilibrium.

I think of myself and all life on the planet as a physical extension of the planet, which is very different from how I thought of it before, as just a surface phenomenon crawling around the planet. We can feel that with plants because they are literally rooted to the earth, emerging from the earth. But that's really true for all life, that’s how life originated in the first place. All living organisms remain in continuity with the planet, so I now feel myself rooted to the garden. It makes me feel a companionship, a continuity, a reciprocity with the plants around me that I didn't quite feel so viscerally in the same way before.

All of us creative people are competing against time, entropy and decay.

-Ferris Jabr

Some of Virginia Woolf’s autobiographical writings were collected posthumously in a volume called Moments of Being. She described these eponymous ‘moments of being’ where she felt like the “cotton wool”2 of everyday life was kind of pulled away suddenly, and she could perceive a deeper reality behind. In one of these moments as a child, she was summering with her family in Cornwall and she saw some flowers by the front door. She suddenly saw this ring connecting the flowers to the earth and realized that the real flower was part flower, part Earth. The true flower was literally continuous with the earth.

When I rediscovered that quote of hers, I was so shocked because it was so resonant with what I've been reading and learning. That is the gist of it really: we are continuous with the planet, physically, materially, scientifically, literally. It’s not just intuition or a trite phrase to say everything is connected. There’s actually a scientific truth there. I'm feeling that on a day-to-day basis in the garden.

I love that. Since I’m always trying to find new metaphors for creativity, I have been thinking a lot about creative ecosystems and how you feed those and how you collaborate with them. Tending to the depleted earth of your garden and helping to bring the ecosystem to life is such a beautiful visual way to think about that. How do you think of your own creative process in terms of how you cultivate it and tend to it?

Evolution is fundamentally a creative process: it is creating things all the time, it is bringing things into being that didn't exist before. It doesn't even matter whether there's intention or consciousness wrapped up with that—it is creative in that very basic sense. There are some parallels with what we do as humans. There is a lot of trial and error in the creative process. You have to try a lot of different things and winnow it down to the things that work, which is kind of what evolution is doing. All these mutations and new things are coming about, and only some of them are actually going to be viable or work, or survive and persist.

That’s what I'm often looking for, ideas that have lasting power, because they have a certain kind of resilience or timelessness to them. All of us creative people are competing against time, entropy and decay. Certain things just don't last very long. They get out into the world and then kind of fall apart after a while. But there are certain ideas that are powerfully resilient, they've survived for so long. I love the idea of an idea being the longest lived thing that we know of, because it can transcend any one individual, or even generation.

It’s challenging to be a professional creative. I often long for the combination of the intense inner creative fire I had in my youth, plus the relative lack of responsibility. It’s a very freeing combination. As a young person, I was so often driven and energized in a way that becomes difficult to replicate with age. Everything was so new and inspiring. Depending on your circumstances, as a child or teen you don't have to worry about paying the rent or utilities or bills, or “what am I doing for my profession and career?” All that stuff becomes increasingly important, increasingly burdensome as you get older. To try and do what you love as a professional and make that your living definitely changes the dynamic. It’s difficult to maintain that space where you have the freedom to pursue creativity for creativity’s sake.

It’s very challenging to define what art is. Sometimes writers take this stance of, “We're not artists, we're professional writers.” I find it hard to draw such hard lines, but I do think there is a fundamental difference between a piece of work that's been created for the sake of creativity and expression, with no other incentives or goals whatsoever, versus something that's being written for money for a specific context to accomplish something beyond just creative expression.

Going back to Emily Dickinson, she was probably a good example of that because so much of what she wrote was in her own bedroom, for herself or for her very close family or friends. It was locked away in a drawer, never intended to be published. That's a very different mode of expression from signing a contract with somebody and saying, “We are writing a book for a general audience that we're going to sell commercially, and it has to be accessible.”

I’m fascinated by creatives who try to navigate those simultaneous and often competing interests. Another favorite writer of mine, Jane Austen, is inspiring in that sense. She was a literary genius doing things on the page that nobody had done before. But she was also a very pragmatic businesswoman, and wanted to make money from her novels. She wanted to supplement her family’s income to a certain extent through her writing. She would get furious with early publishers who just held on to her manuscripts and refused to do anything with them. I feel like we're all forced to negotiate similar tensions and dualities in the modern age, as creative professionals. I'm fascinated by those dynamics, and I feel like I'm constantly struggling to find the space and the time to create for creativity’s sake.

Absolutely. I'm glad that you said that thing about artists and writers because I have two questions I always ask people. We’ll start with the first one: what does it mean to be creative?

I think like you were intimating earlier, creativity is a human universal. To be human is to be creative. To have a self-aware mind necessitates some amount of creativity. Simply putting words together in new combinations to communicate with other humans is a form of creativity.

Whether it's writing, speaking, cooking, or any number of things that we all do as humans, there's creativity infused in all of those activities. Creativity was so important to our early evolutionary history as humans as well. You could almost recast human evolutionary history as a long unfurling process of creativity, learning to use things in new ways or to make things in new ways and improving on them bit by bit.

The raw materials of the planet are available to all life forms, but different life forms use them in very different ways. We humans excel at exceptionally creative uses, like this computer through which I'm talking to you right now. This is rock and crystal and mineral and electricity. This is all stuff we've gathered from the planet around us and turned into this incredible device that no other life form has ever made. It kind of becomes magic when you think about it.

To be creative is to put something into the world that wasn't there before. That can take the form of conceiving something, whether an idea or a material invention, that never previously existed. Or it can take the form of expression: articulating something that has never been expressed that way before. That's how I think of creativity.

I usually ask, “what does it mean to be an artist?” and then for this interview I switched it to “what does it mean to be a writer.” But based upon what you said earlier, I guess I should ask both!

This comes up a fair amount in the journalism world because some reporters and journalists are not comfortable calling themselves writers. Some writers are not comfortable calling themselves journalists, because they don't think what they're doing qualifies as journalism. Some people who write about nature and science don't like to call themselves science writers because that sounds too official or too scientific for them.

I tend to be very comfortable with all of the labels simultaneously because I find it hard to fully disentangle them. I think that if you are a journalist working in print—words on any page or screen—you're a professional writer, and I don't know what else to call that. If you're engaged in the process of reporting, of going out into the world, talking to people, interviewing, documenting, then you're engaged in journalism. I'm not sure what else to call that either.

The art part becomes a little trickier because people have really intense opinions about that one. As somebody who loves literature, I often ask myself, “Am I making literature? Am I making art?” How do I distinguish between professional writing that is or is not literature or is or is not art? It’s very challenging for me to find a line to distinguish those things.

I very much hope that at the very least I'm infusing everything I write with a lot of artistry. People use that term differently—sometimes they’ll talk about somebody's craft or lyricism or artistry, without saying that a book itself is art. But I do think that most creative nonfiction writers are engaged in a process of art.

There's a sort of privileged form of art that is unencumbered by other restrictions, goals, or incentives that we were talking about before, and anybody can access that by just going into a room by herself and creating just for the sake of creating. I guess that is art in its purest form, but it's very difficult to do that full time as a professional in today's world. It’s hard to think of any famous artists who were truly, fully removed from any of those incentives or external influences.

It makes me think of the idea that just like Earth is alive, there's a back and forth relationship between all kinds of systems, including within the creative sphere. These things are interconnected, and they fuel, feed, and inform each other. Trying to pull just one thing out doesn’t serve us because then we don't see those other connections. One more question for you. There’s a beautiful line in the epilogue: “We are neither the cancer of the Earth nor its cure. We are its progeny, its poetry, and its mirror.” I want to know how long that sentence took to write because it's so beautiful. But my main question is, after working on this book, how are you thinking differently about humans and the Earth? What are some things that we as a culture have not been thinking about that we need to be paying a little more attention to?

That sentence was one of those rare moments where it just kind of pops into your mind from some mysterious creative well. It wasn’t really a very conscious deliberate process.

Writing this book has absolutely changed how I think about humanity and our relationship to the planet. I think there's a massive difference between thinking of ourselves as inhabitants of this world versus continuous with the world, a literal extension or expression of the world.

I really don't like this “passengers on spaceship Earth” analogy. I find it's too alienating, it segregates us from the planet. I think that the challenge for us right now is that we have to recognize that, on the one hand, we have an outsized influence on the planet, but on the other hand, there's no way we're going to be able to control something that complex in totality. For me, that means pulling back, trying to do as little damage and harm as possible. When we do actively intervene, to do it as informed and intelligently and carefully as possible.

That's what is so amazing about something like renewable energy. One could imagine an alternative human history in which we pursued renewable energy and the coal-powered Industrial Revolution never happened, and what our world could look like today. Yes, there are challenges—like all the specialized minerals that are needed for certain forms of energy—but compared to fossil fuels, the level of extraction is so much less. The amount of harm to the planet and human health is so much lower.

We need to think about how we emulate and amplify the planet's innate ecological rhythms. I don't hear that kind of language in a lot in current climate discussions. The planet already has its own stabilizing ecological rhythms, which have coevolved for billions of years. There are many things we can do that support them or strengthen them. Conserving, restoring, and preserving ecosystems is one of the major ways to do that.

Looking at these nature-based solutions, minimizing our disruption of planetary rhythms, amplifying those stabilizing feedback loops that are already built into the Earth system—these are things that I think we need to look much more seriously at doing.

And more gardens!

And more gardens!

Thank you so much to Ferris for this conversation—I am still thinking about a lot of what we talked aboutt. Be sure to check out his book Becoming Earth.

Check out more Creative Fuel interviews here.

RESOURCES + INSPIRATION

Whenever I do an interview I ask for a list of recommendations, to see what people are reading and paying attention to. Here is what Ferris has on his radar right now.

The Mountain in the Sea by Ray Nayler is the best science fiction novel I have read in recent memory

I've just started reading the haunting and lyrical A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ni Ghriofa and am really enjoying it so far

I'm also reading Dodie Smith's enchanting I Capture the Castle for the first time

I recently visited Mark Twain's house in Connecticut, where he and his family lived in his later years, and I was taken with the gorgeous, geometric, nature-inspired wallpapers and textiles of 19th-century interior design pioneer Candace Wheeler. You can see her spider web ceiling and bee wallpaper designs here, which feature in the house.

Upcoming Creative Fuel Workshops + Events

No live workshops this month, but you can catch up on all the 2024 Create+Engage workshops!

The Fall 2024 session of DIVE writing group kicks off in October and you can sign up now. Gather together with facilitator

and other likeminded souls and make fall a season of writing. Yes this feels so far away, but think of it like an early present to yourself. More info + sign up.

Do you enjoy Creative Fuel? You can support this work by becoming a paid subscriber. You can also order something in my shop, attend one of my workshops or retreats, or buy one of my books. Or simply share this newsletter with a friend!

Woolf wrote, “As a child then, my days, just as they do now, contained a large proportion of this cotton wool, this non-being. Week after week passed at St Ives and nothing made any dint upon me. Then, for no reason that I know about, there was a sudden violent shock; something happened so violently that I have remembered it all my life”

Anna, this post resonated in every corner of my soul! Thank you deeply.

I feel that my creative being has been submerged in recent years under a buildup of political concerns and mere survival.

I plan to read “Becoming Earth,” and look forward to chasing down more about Candace Wheeler. It’s been a wonderful trip down a creative rabbit hole! 🐇

See you soon.

Fascinating interview and topic 🤗thank you