Prescribe Yourself Some Art

The "forgotten fifth pillar of health."

Remember: art makes life better. // Salish Sea garlands are back in stock // Kerri Anne is leading a three-part writing workshop centered around food and memory. More info here.

Since I am in my early 40s, every single piece of wellness advice the algorithm serves me has to do with protein and lifting weights. Protein I am not convinced by (most of us are already eating too much of it), but the weights I know are good for me. Strength and brain health and all of that.

When it comes to healthy living, we all know we need to eat well and move our bodies. Not to mention spend time with our friends. Universal healthcare would also help—healthcare should be a human right, not a luxury pursuit. But in all of our wellness efforts and attempts at living healthier lives, as a society we have missed an essential component: art.

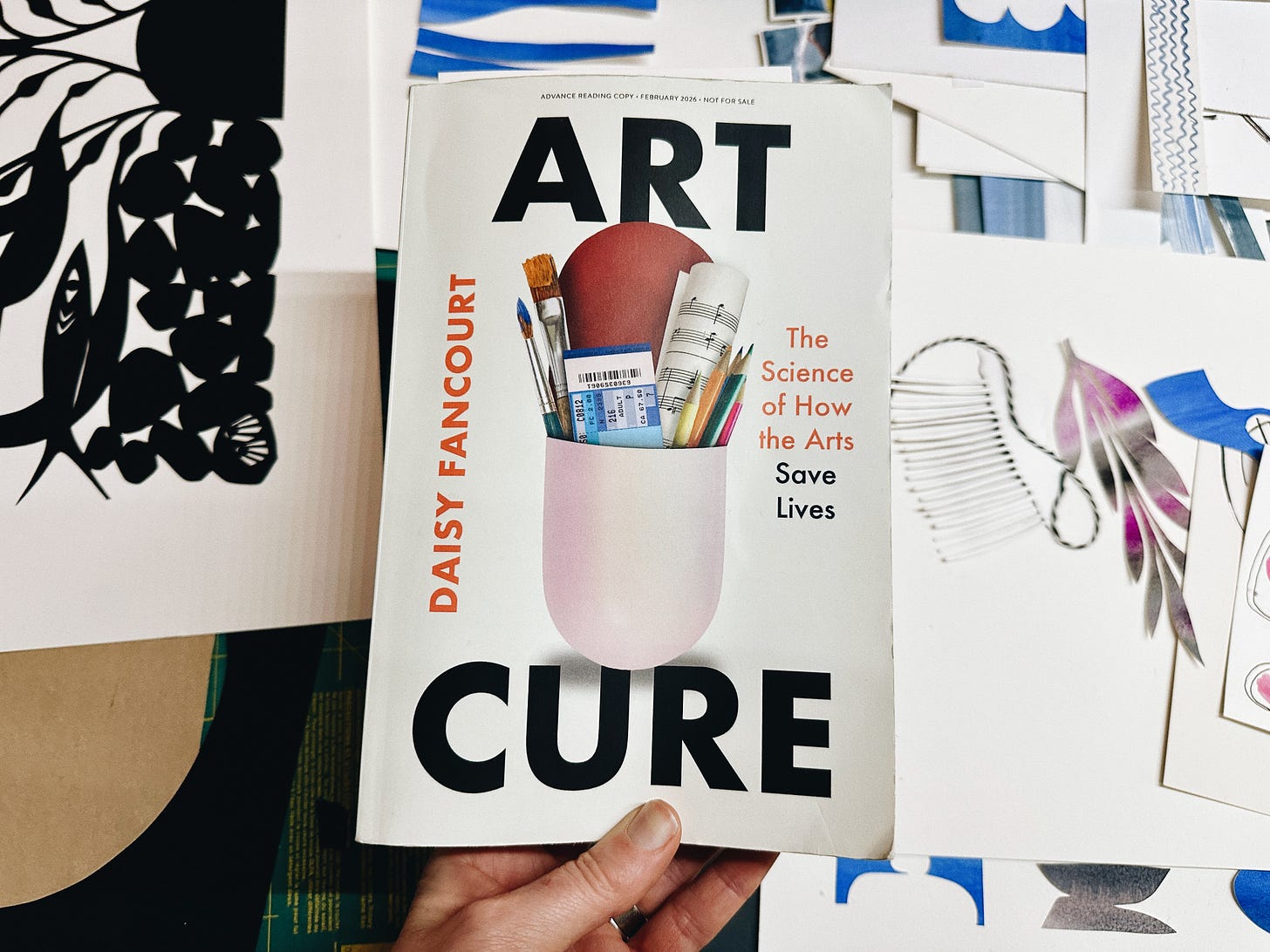

In her new book Art Cure: The Science of How Art Saves Lives, Daisy Fancourt takes us on a deep dive exploring why art is good for us, arguing that art is as essential for our health and well-being as sleep, food, and exercise. She calls it the “forgotten fifth pillar of health.”

Fancourt is a professor of psychobiology and epidemiology at University College London, and for more than a decade has been working with governments around the world to “prescribe” art. Why should we consider art as prescription? Engaging with art and creativity, even for just a few small stints every week, can have powerful effects on our physical and mental well-being.

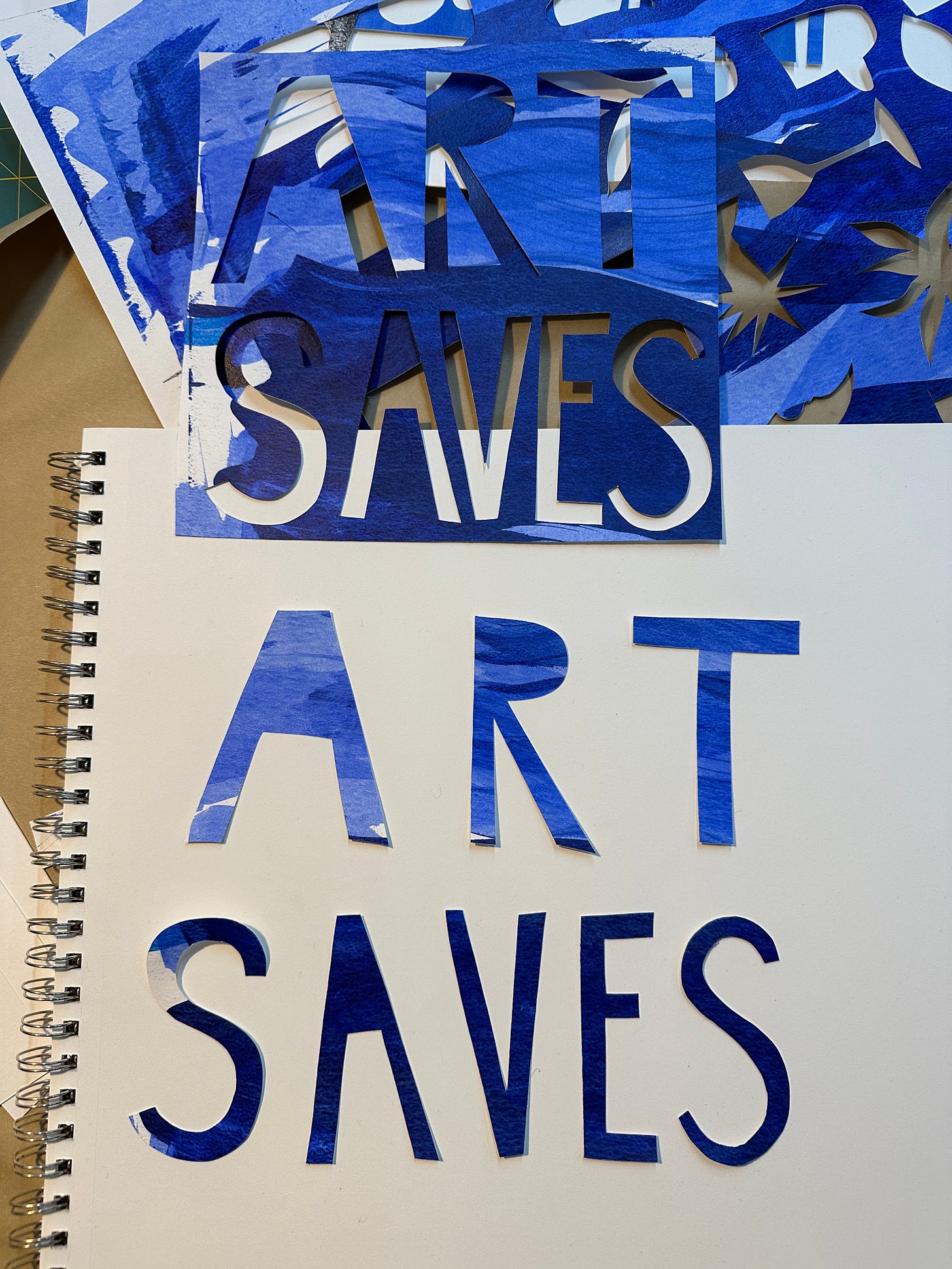

Those of us make and engage with art probably already intuitively know this. I know I do. Art is a place to come to when I don’t know what else to do with my emotions. Making something with my hands almost always has a calming effect.

What we intuitively feel and know also has an extensive and growing body of research to back it up, and Fancourt’s book helps to give us the how and why behind the power of art to make us feel better. Amazingly, there is no physiological system in our bodies that art doesn’t affect. Our brain, our breathing, our movement—they can all be activated and impacted through engaging with the arts.

Let’s start with the most obvious link between art and well-being: it makes us feel good. Art activates regions of the brain that are essential for our pleasure response, the same parts of the brain that light up thanks to food and sex.

That sense of pleasure in art can come from the “peak moments”—like a chorus that comes back repeatedly in a song, or the climax in the plot of the novel. But it’s not just those moments that activate our brains, it’s also the anticipation of those moments. When we expect that moment of resolution to arrive and it doesn’t, we keep wondering when it’s going to happen, causing our brain to feel a bit of tension—it keeps waiting for that hit of dopamine it’s expecting to get. Fancourt writes, “the higher the discomfort during the tension phase, the higher the pleasure when we finally get to our resolution.” Consider the twists and turns that happen in a good murder mystery, when you think things are going to be solved, but there’s yet another unexpected plot line. Or a “drop” in dance music. When the clue is finally found, or that drop finally hits, it’s incredibly satisfying for your brain.

Art also helps us process and understand our own internal worlds better. Consider how good and cathartic it can feel to a really sad song. This is known as the “tragedy paradox.”

“In real life, we tend to do everything we can to avoid negative experiences,” says Fancourt. “But in art, we’re paradoxically drawn to them.” Think sad songs, paintings full of anguish, horror movies. “We really seem to revel in those negative emotions,” says Fancourt. Experiencing this kind of art allows us to do a kind of simulation—feel and experience those emotions but without needing to act on them. This “allows our brain to kind of put those emotions on a pedestal and observe them, contemplate them, almost like in a museum,” says Fancourt. “It helps us to practice managing the emotions and even imagine how we might deal with things in our real lives.” A kind of workout for your emotions. Add that to your strength training routine.

Art has significant physical impacts too. It can help to boost immunity, even help keep us feeling younger. Fancourt and her team have found that adults over forty who engage in the arts every week—whether that’s making, listening, watching, or visiting—are about one year biologically younger than their counterparts. Tell that to the longevity tech bros.

In The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron writes, “art opens the closets, airs out the cellars and attics. It brings healing.” Research shows that there’s a strong link between art and mental health, helping with depression, anxiety, and even helping to build brain resilience against neurological conditions like dementia.

Pairing arts with mental health treatment can have particularly powerful impacts. In a study in Finland, adults with clinically diagnosed depression received either standard care (psychotherapy, medication, and psychiatric counseling) on its own, or that same standard care with the addition of music therapy. After just a few months, the group that received the music therapy were three times as likely to have improved their depression and anxiety scores.

Art is an integral part of our experience of being human—creativity, art, and self-expression are things we have been doing since our ancient ancestors. As Fancourt writes, “we are a planet of 8 billion artists.” We have unfortunately pushed arts to the side, and to our detriment. Instead of thinking of art as a core part of our well-being, we see it either as luxury or entertainment. We’re “lapsing into a state of artistic passivity.”

Reading Fancourt’s book, it’s clear that there are so many health, social, and even economic benefits to having more art in our lives. Not only does the evidence show how beneficial art is to our health, it’s also enjoyable. There are plenty of not-so enjoyable things that we do for our health all the time. Which really leaves you wondering why as a society we don’t invest in it more.

I asked her this question. “I’ll be totally honest, I really don’t get it,” she told me.

For tens of thousands of years, art has played a central role in humans’ lives, but how we view that relationship has shifted. “In certain countries, particularly the US, the UK, the global north, we’ve started to create arts into a kind of leisure space that becomes associated with professionalization, institutionalization, and therefore needing money,” says Fancourt. We have turned it into “a paid commodity, rather than a day-to-day practice for many people.”

“Surely AI should be doing the tasks that we don’t want to do.

Surely our time should be for the fun creative tasks like art.”

- Daisy Fancourt

When it comes to maintaining health, a day-to-day practice doesn’t have the same financial allure as drugs and medication. There’s no great pharmaceutical industry profit to be made from arts classes. I can just see the ad: Feeling down? Have you tried ART? Side effects: a desire to spend more money on supplies.

Fancourt writes in the book:

“Can you imagine if a drug had the same catalog of benefits as the arts? We would be telling everyone about it, fighting to get our hands on it, paying premium prices, taking it religiously every day, investing trillions into further research and development. It would be revered as our elixir.”

I think the resistance to arts may run even deeper. Self-expression and creativity are a powerful way to challenge the status quo. Artists are an unruly and unpredictable bunch. That doesn’t work well in political systems that want to control and subdue. De-vesting in the arts is a way of exerting control, ensuring not too many questions are asked, avoiding any pushback.

No wonder there has been great investment in AI and creativity, turning the creation of art into a soulless matter where it’s easy to control the outcome. In pursuing speed, optimization, and technology, we’ve pushed the human part of the creative process to the side.

If you consider the importance of art all throughout human history, that begins to look like a very failed approach.

“Surely AI should be doing the tasks that we don’t want to do. Surely our time should be for the fun creative tasks like art,” Fancourt told me. “But also, given that a lot of AI is using things like large language models that are about predicting what’s most likely to come next… that’s the opposite of what art does. Art is often challenging, it’s making us think in different ways, bringing new perspectives into society. Surely, we should be saving art for the humans. It’s one of the crowning achievements of our species.”

Fancourt notes that she sees a cultural pushback to some of this. Gen Z is embracing “granny hobbies” (yes, you can roll your eyes at this term). Craft and art events are growing in popularity. We have an inherent need to create, and clearly in an attempt to digitize, streamline, and optimize our lives, many of us are craving the more tactile, slow creative activities that actually make us feel good and give us a sense of satisfaction.

If we want the benefits of the arts, we also have to learn to savor. There’s a clear difference between sitting down to listen to an album as opposed to having music on in the background, just like there’s a difference between quickly scanning a piece of art in a museum instead of spending time with it to really look and feel. On average, people in museums only spend about 28 seconds in front of a piece of art, and much of that time goes to taking a picture of it. Attention is coming a scarce commodity. We have to take time to get more than just a surface impression.

In tough moments, art can offer respite. But it’s also not a quick fix, nor should it be. Arts deserve to be woven into our everyday lives.

“I don’t think we should be heading down the extreme spectrum of trying to kind of biohack our arts experiences,” says Fancourt. “I talk about companies that are trying to use AI to come up with the perfect relaxing music, but why? I don’t believe that is even possible. I think that’s actually completely flawed as an idea.” When we do that, “we’re trying to make art a pill that we swallow, but that completely undoes the point that art is such an enjoyable behavior.”

More art, more attention, more humanness.

That’s a prescription I can get behind.

-Anna

ANALOG INSPIRATION: NATURE ART

I have assorted beach rocks in pretty much every pocket of every jacket, backpack, and purse that I own. There is a certain grounding feeling that comes with the weight and texture of a rock in your hand. Something to hold you in place for a moment.

I got to spend some time on a beautiful rocky beach last weekend, and I love finding rocks with lines in them and making them connect. You may not be close to a beach, but any kind of nature art is the perfect trifecta of making you feel better: being outside, paying attention, making art.

Orion Magazine is hosting a conversation with Ross Gay and Aimee Nezhukumatathil on Thursday February 12th in celebration of the second edition of the publication Earthly Love. Sign up here.

I will always read Sarah Menkedick whenever it arrives in my inbox. This essay on immigration, power, and fear is essential reading.

Children’s drawings turned into chairs.

I finally read Lily King’s Heart the Lover. So good.

I really enjoy Rebecca Solnit’s newsletter.

This is such a great piece, written with so much thought and care. This remark specifically stood out to me: “I think the resistance to arts may run even deeper. Self-expression and creativity are a powerful way to challenge the status quo. Artists are an unruly and unpredictable bunch. That doesn’t work well in political systems that want to control and subdue. De-vesting in the arts is a way of exerting control, ensuring not too many questions are asked, avoiding any pushback.”

Thank you, Anna, for this and all you do!