How are We Paying Attention?

Thoughts on living in the attention economy as well as lessons from artist Kristin Link on using our creative practice as a way to be more observant.

Creative Fuel is a newsletter about the intersection of creativity and everyday life. There are essays, prompts, Q&As, and more. Paid subscribers help to bring this newsletter to life.

The other morning I was sitting and drinking coffee at the kitchen table. NPR was on, as it most always is in the morning, the news playing quietly enough that it wasn’t overpowering, but loud enough that it wasn’t entirely possible to ignore. I mindlessly grabbed my phone to look at whatever thing I should know better than to look at while sitting at the kitchen table (email or Instagram most likely). My brain partially picked up on the fact that there was a story about the earthquake in Turkey and Syria and the reporter was interviewing a Syrian woman. My thumb casually touched my phone screen ready to scroll, and I heard the woman crying. I stopped. “Pay attention,” I thought.

I put the phone down, I turned and faced the window and looked out as I focused on listening to what the woman was saying. By the end of it, I too was crying, her words and emotions garnering a human, empathetic reaction from myself.

It occurred to me later on in the day how much I have been shutting out lately. That parts of me have become numb to news and daily events. That it’s easiest to turn off and tune out, mindlessly pick something else up to hold my attention. I pass through instead of participating.

On the one hand, this is a coping mechanism. If our hearts and minds took in every single tragedy at their full extent, we might never do anything. But entirely blocked and closed off? That doesn’t allows allow us to open up and dig into the wells of empathy that we are all capable of.

As the week went on, I kept thinking about attention—where I was directing it, where it was lacking, where it felt like maybe I could have more. At a reflective writing workshop that I took from Katherine May, she noted that “capacity” might be a different way to think of “attention span,” which certainly resonated. What do we have the capacity for? The capacity to listen to? The capacity to look at? The capacity to feel?

Our capacity can feel overwhelmed and overloaded a lot of the time, and there’s a lot of talk about attention spans. As a culture, we certainly perceive a reduction in our attention spans (although, we also think we check our phones less than we actually do). However, there is currently a lack of long-term studies that would help us to better understand our attention and whether or not it’s decreasing. Not to mention that attention is variable depending on the task at hand.

Yet there’s no denying that in this day and age, there is more pulling at our attention. We live in an attention economy, and “… a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention,” as Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon noted. Research from cognitive psychologist Gloria Mark shows that we spend about 47 seconds on a task on screen before switching to something else (it was around two and a half minutes back in 2004).

There is simply so much that we could be paying attention to and the digital tools make it so easy. As Mark told The Guardian, “we’re having such a hard time controlling our attention, because we haven’t figured out yet how we can integrate this technology in our lives, and use it wisely.”

That amount of information in every corner, at every hour, has an impact. A 2019 study argued that because of social media and endless news cycles, our collective attention is dwindling. Not to mention that our inherent negativity bias impacts the kind of attention that we give to something, which sort of ensures that we’re going to dwell on all the bad things we see and read.

We click, we scan, we scroll, we repeat. Existing in these round-the-clock news cycles and updates with constant access to digital devices does have an impact and we can feel it. We start to feel frazzled, disjointed.

In the last couple of months I have read anecdotes from people who have been excited to sit down and read a book, only to find themselves one page in and picking up their phone to look at something else (and of course, now I can’t find these examples, because I can’t even remember where I saw these anecdotes in the first place). It’s what leads us to click on headlines like, “How to Focus Like It’s 1990.”

One of my favorite books on the topic is How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy by Jenny Odell. As Odell writes:

“One thing I have learned about attention is that certain forms of it are contagious. When you spend enough time with someone who pays close attention to something (if you were hanging out with me, it would be birds), you inevitably start to pay attention to some of the same things. I’ve also learned that patterns of attention—what we choose to notice and what we do not—are how we render reality for ourselves, and thus have a direct bearing on what we feel is possible at any given time. These aspects, taken together, suggest to me the revolutionary potential of taking back our attention. To capitalist logic, which thrives on myopia and dissatisfaction, there may indeed be something dangerous about something as pedestrian as doing nothing: escaping laterally toward each other, we might just find that everything we wanted is already here.”

As humans, we experience attention and distraction differently. Attention comes in different forms, and in the creative process we don’t just need one type. We benefit from broader forms of attention—the ones where our brains take in a variety of things, daydreaming, going down some rabbit holes, getting distracted by another idea, etc.—as well as more focused ones.

I think most of us know that once we’ve done all that gathering, marinating, and mind jumping, when it’s time to do the work, we’re required to sit down and focus, at least for a bit. Creativity isn’t just the daydreaming or the ravenous curiosity or the diligent time at the desk, it’s all of it, and all of the spaces in between.

Which means that in an attention economy, what we commit our attention to and how we commit our attention matters.

When we commit to observation, we challenge our preconceived notions and start to pick up on all kinds of details. We start to make connections. We show up in a different way. When we pay attention to the big things, we’re required to sit with them, hold them, and not just pass by. When we pay attention to the little things, we begin to see our immediate world expand. We can work at finding the extraordinary in the mundane.

When we start to pay more attention in one place, it expands our capacity to do so in other places. It requires us to actively take part, instead of just passing through.

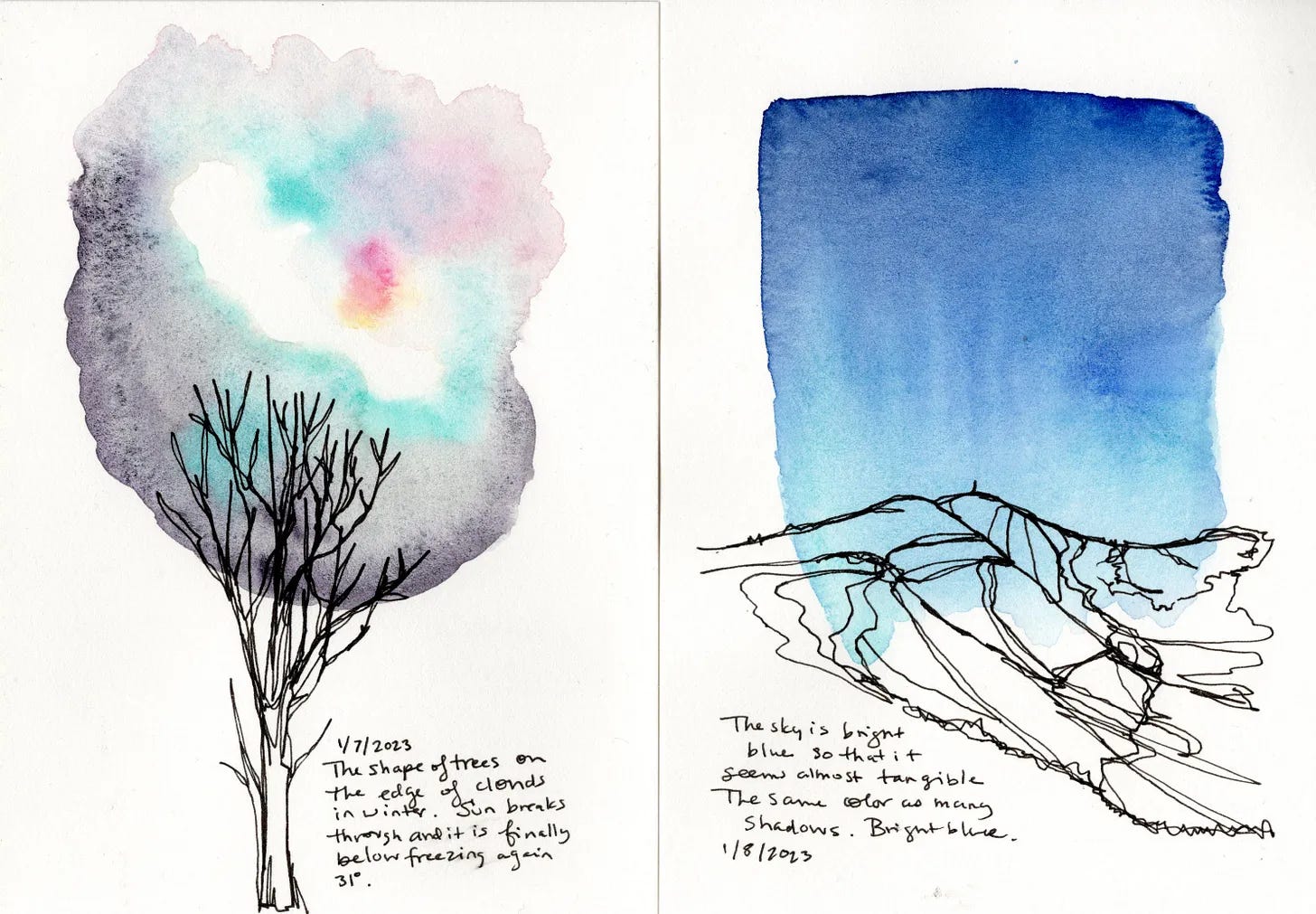

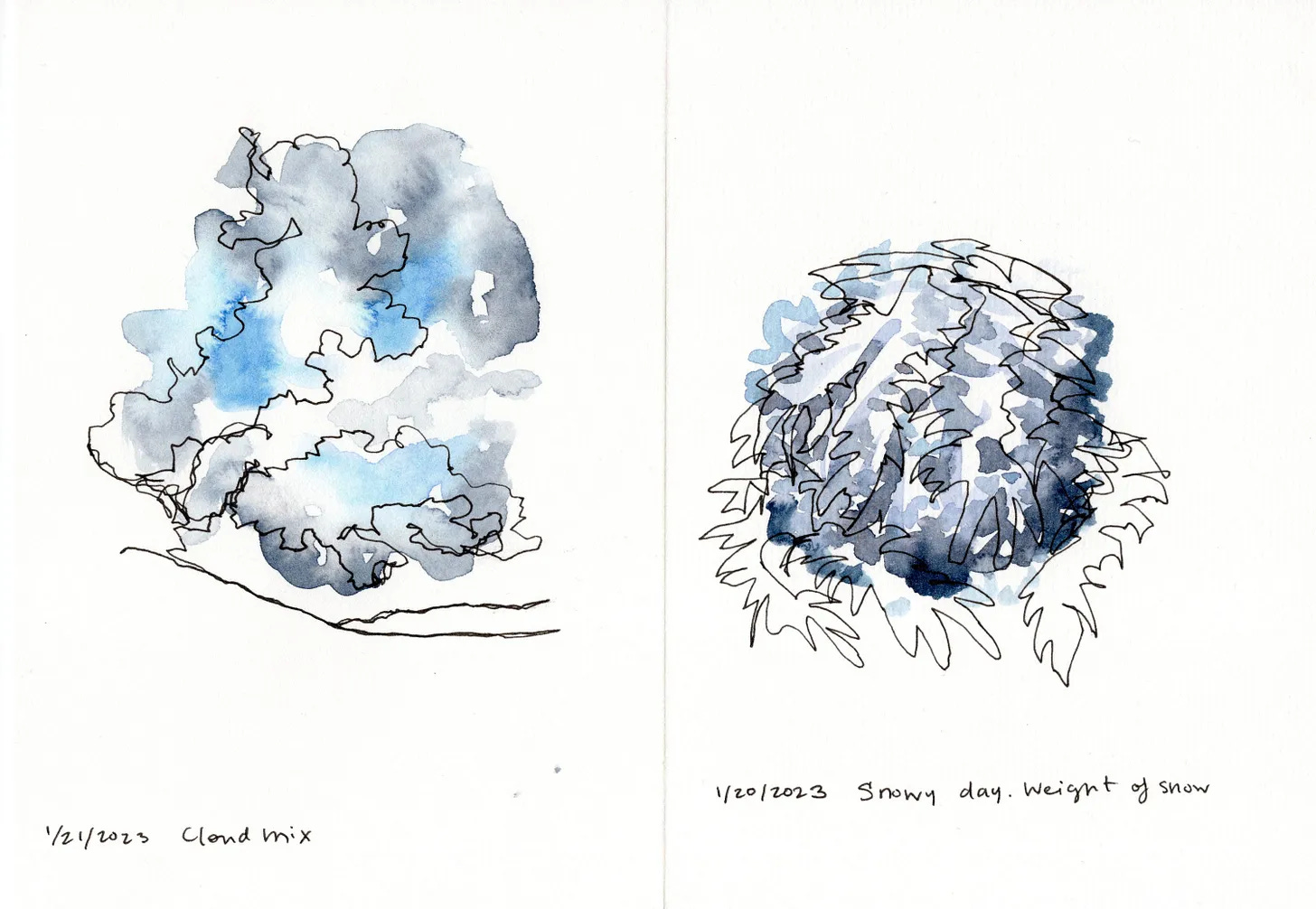

With that in mind, today I am bringing you an Q&A focused on attention and observation with artist Kristin Link. Whatever your medium, I hope that it helps to spark some ideas of how honing in on your creativity also just might help you to hone in on what’s around you and vice versa.

To actively choose what you’re paying attention to.

Practicing Curiosity and Observation: Q&A with science illustrator and natural history artist Kristin Link

Art and media have the ability to influence our empathy, which makes it even more important to think about what we engage with, what we consume, what we take in. But I have also been thinking a lot about how art and creativity can be a tool for encouraging us to be more observant of the world around us, or at least give us a filter for directing our attention. One study even showed that engaging in creativity just might help us to expand our attentional capacity.

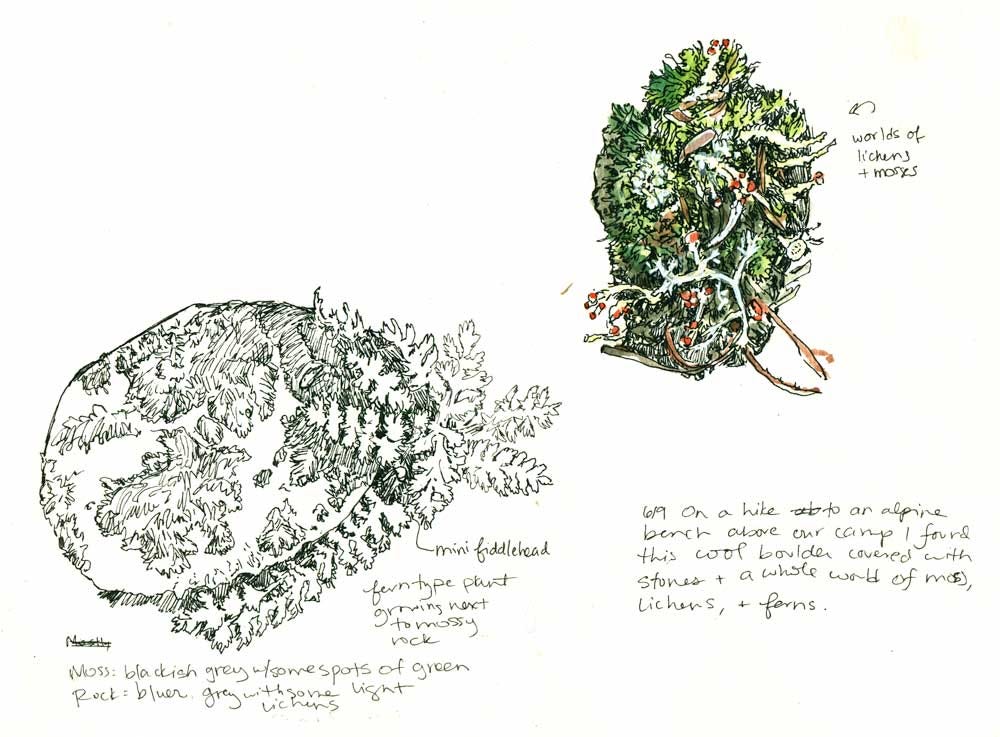

There’s perhaps no better concrete example of this than artists who do nature journaling or field sketching, a creative practice that is built on a ritual of being observant.

I’ve been following the work of Kristin Link for quite some time, and have been enjoying her new newsletter Weekly Nature Journal. Kristin works as a science illustrator, fine artist and educator, and her work beautifully captures the whole spectrum of nature, from the intimate to the bigger picture. We connected to talk about her process, finding inspiration in the natural world, and the art of observation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Anna Brones: How did you get into ecology, environment, and art? Did one inform the other?

Kristin Link: I always loved science, art and the outdoors. I definitely didn't grow up feeling like being an artist was the best career choice, as far as what society told me. But I also grew up with a lot of encouragement to pursue the arts. So because of that, I just kept wanting to do it and making time for it and making space for it in my life, and then realized that was probably my favorite way of working. Science illustration seemed like a cool way to combine my interests.

Scientific journaling and drawing has been something that people have been doing for a long time to document and understand the natural world. Is that something you were already doing before you went to school? How did you get into nature journaling?

One of the first classes that was part of my science illustration program was on field sketching. They were all great classes. But that was the best class ever. It really combined all those things I was interested in, including the aspect of being out, or being with the subject. After I took that class, I was like, “I want to teach this, I want to share it with as many people as I can, and spread it around.” I think that nature journaling definitely has grown a lot as a community and a practice as well, which is cool, because there's more people doing it.

Why do you think that is?

I think partially because of the pandemic. People were at home and looking for a way to engage with their surroundings. I think also because of John Muir Laws. He went to the same program I did, and I think had the same similar epiphany. He's a really talented teacher and educator and figured out a whole way to make a curriculum out of it and bring it to schools and make it accessible to a lot of different people. So I think his work on that has grown a lot of community around it as well. Because he has been generous with his knowledge and experience, others have done the same, so there is a pretty cool community of nature journalers all over the world.

I get the sense through your art that you’re paying attention, but that also you’re very consumed and interested in a variety of elements and aspects around a scene. I am wondering if you have a memory of the first time that you felt really curious about something?

I think I've always been a kind of person who was really interested in natural things, and also kind of a quiet, observant person. I remember as a kid, mostly just being outside and kind of having these like secret little places that I could go to, and just spending time there. Like, in the woods, or making a fort or not even making a fort, but finding a place under a tree. No one knew where I was, and it was that feeling of being alone and really in tune with what was around me.

I think in loving doing that, I realized that when you are still and quiet, you notice different things, different things happen in the world around you. Instead of being really curious and asking a lot of questions about things, what really draws me or did, especially when I was younger, was that process of just being surrounded by nature and kind of in my own little secret world of discovery.

I have this vision of you every single day outside doing field sketches. But what does your actual practice look like?

My relationship with daily practice is kind of weird. I've been doing that daily drawing practice. And even that, I'll skip days and catch up. My goal is to think about it every day and think about and figure out what I want to do. So if I do that, I'm happy with that. I definitely spend time outside every day observing, so that's definitely a daily part of my life and making art is usually as well, but I don't draw necessarily every day. I've tried and sometimes I think I want to and sometimes I've been able to do it, but I'm just not fighting with myself about it.

I love sketching outside and I love sketching from life but I don't do all my sketches from life. I think that drawing from photographs is also a great tool. And I know when I do that I also practice a lot of observation skills and memory skills and use those in my artwork as I'm doing it. There's no right or wrong way to do it. One great thing about being an artist is that we get to kind of like make up our own rules.

Do you think your art practice helps you to be more observant?

I actually don't even know if the art practice is what comes first, but it definitely feeds into it. I enjoy spending a lot of time being reflective and being observant. So I think those are just things that I am going to do no matter what, whether I made drawings about it or not. The art is another way to pursue that. It can be very meditative for me where I'm not really thinking about myself while I'm doing it. I'm just totally losing track of time and paying attention to the thing that I'm drawing and that is wonderful. I love that feeling. But then it's also that I can be intentional with it, and practice asking questions or practice paying attention to something. And then if I'm doing that with my art, that definitely filters into other things as well, like things I'll notice.

One thing John Muir Laws always talks about is “practicing curiosity” and going outside and asking questions. And I never thought of that as something that you could practice and get better at. But when I've done it myself, I found that it works. Even just walking around, maybe not with my journal, but just going outside going for walks, I'll see things and start thinking, “oh, I wonder why that's like that, or what caused that?”

I love that, a practice of curiosity.

Wendy MacNaughton says, “drawing is looking, and looking is loving.” When you’re looking through the internet you’re kind of judging, you’re looking through and thinking “am I going to tap the heart, am I going to comment, or share it, or what am I going to do?” But when we’re drawing we’re just being with the subjects, or whatever we’re drawing, whether it’s people, or a place, or a feather. Even if it’s something that we didn’t think was that interesting or that beautiful when we started drawing it, a lot of times that process of paying attention builds appreciation and that seems like the opposite of online distraction, looking through things and deciding what to pay attention to.

When I was a student and people were telling me what to draw, what they chose was not what I would pick. But the more time I spent with it, I was always amazed that I did kind of build a relationship with it, and that would be something that would be interesting to practice: find things you don’t want to draw and draw them and see how it makes you feel.

For someone who is looking to get into a field sketching practice, or just more observational nature drawings, what are some tips for starting out?

I try and think of exercises that I can do so that I'm not so invested in the end result. Setting up that space for playing. I'm usually trying to not complete a whole drawing. Breaking it down: “I'm going to focus on a line” or “just go out and draw a bunch of textures or collect a bunch of different colors.” Daily practices that feel like they take a lot of the pressure off, so I'm not so invested in the product, I'm invested in the process.

There's a lot of different ways to be outside and observe what you find. Leaning into what you are interested in, and how you like making recordings is a really good place to start. Paying attention to that, and figuring out what your visual vocabulary is, and how you like making marks and interacting with the page, or maybe it's videos or whatever you're doing. For me, I like drawing. And so that's kind of where I go with it.

Breaking something down into different components where I'm not so worried about creating a drawing that represents one thing is really helpful for me. Focusing on making a page of just observing different colors, or observing different textures, and separating out those processes is a great practice. I love making those abstractions of the world around me. That's a cool place to start that kind of takes off some of the pressure off.

One thing that's been really helpful for me is separating [elements] out, figuring out how to draw the form of the main shape overall, and then coming in and looking at the details later, because I think those are definitely two different parts of my brain process. Sketching out the main form and then thinking about detail has been really helpful.

USING CREATIVITY TO CULTIVATE ATTENTION

I hope that exploring Kristin’s work inspires you to use your own creative practice to do some more observation, or pay attention to the world around you in a different way. I really like her current daily drawings combining color and line work, and it has inspired some pen and color work in my own sketchbook.

Be sure to sign up for Kristin’s newsletter.

Tomorrow I’ll be sharing another weekly creative prompt for paid subscribers all about paying attention. If you want it in your inbox, be sure to subscribe.

10% of my shop sales and paid newsletter subscriptions this month will be donated to International Rescue Committee and Syrian American Medical Society in support of aid efforts in Syria and Turkey.

The two descriptors that resonated with me a “practice of curiosity” and “process of paying attention builds appreciation” - I will be thinking about this Q&A! Thank you for introducing me to this artist.

I've been a fan of Kristin's work for a while now and I love seeing her here. I particularly love how small this world of creative, people-who-pay-attention types really is. I love all the overlaps!