Cults, Influence, and Truth as Creative Constraint

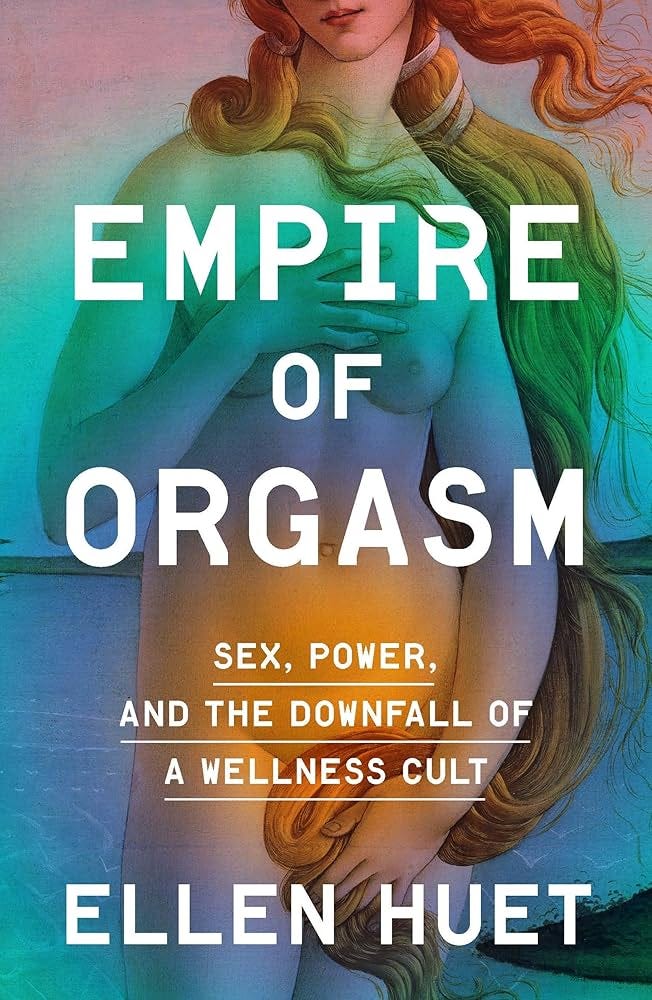

A conversation with Ellen Huet, author of Empire of Orgasm: Sex, Power, and the Downfall of a Wellness Cult.

Writing in the Deep writing workshop with Kerri Anne starts on Monday, sign up here. // The 9th edition of 24 Days of Making, Doing, and Being digital Advent calendar starts on December 1st — all you need to take part is a paid subscription.

Hello friends,

Today I am bringing you an interview with Ellen Huet, author of the book Empire of Orgasm: Sex, Power, and the Downfall of a Wellness Cult which is out this month. The book documents the story of OneTaste, a company started by Nicole Daedone which aimed to bring the practice of Orgasmic Meditation (yes, “OM” for short) to the masses in the name of wellness, empowerment, and cultural change. What ensued was a trail of manipulation and trauma, a charismatic leader taking advantage of people’s vulnerabilities, often at a great emotional and financial cost.

You might be thinking to yourself, “A book about a cult? Isn’t this a little different than the usual Creative Fuel topics?” Sure, it’s the first time I’ve mentioned cults in this newsletter. But I’m certain it won’t be the last. Like lots of people, I am fascinated by cults and what draws people in.

Cults are an interesting lens for looking at our current culture. What do they say about our collective craving for answers to big questions and our ability to follow people to the ends of the earth when they tell us they have them? What happens when we lose our trust in institutions and put it into individuals instead? What happens when we stop seeing nuance and only expect black and white answers?

As Ellen writes in the book,

“…since the 1970s, some of the fastest- growing cults have focused not on religion but on a secular path to self-improvement. They promise members psychology-based teachings for personal growth, satisfaction, and prosperity—a welcome anchor in a cold and unmoored modern society.”

That’s not just cults, it’s the currency of our modern economy where influence turns to gold. Any advice can be packaged and monetized, whether it’s in a container of supplements, a method for success, tips on how to live well, or answering the messy questions of what it means to be human with simplified five step equations.

It’s easier to sell enlightenment than it is to be enlightened. Just like it’s easier to complain about how something is broken than doing the work of fixing it. Easier to dole out advice that brings you a profit than quietly walking the path to changing yourself.

Ellen and I met a few years ago at an annual gathering put on by friends to give the space, time, and community for working on creative projects. Over the course of that time, Ellen was deep at work on the book, so we’ve commiserated over the years about the writing process and all that it entails. I’m excited that she’s finally at the finish line and that this book has come to life.

OneTaste pitched Ellen to write about the organization in late 2017. At the time, Ellen was reporting on startups and was intrigued about the idea of the pitch, a sexuality wellness startup with a woman at the helm. One conversation led to another, and soon Ellen was reporting a very different story. This one was far messier, complex, and traumatic than what the PR talking points had summed up. She exposed this darker side of the organization in her 2018 piece for Bloomberg, kickstarting a cascade of not only other media about OneTaste but also a federal investigation.

The publication of the story encouraged more former OneTaste members to come forward and talk to her. By the fall of 2020, she had signed a book deal.

“I had all these optimistic timelines,” Ellen told me. “I remember thinking the book was going to come out in 2023. That was clearly incorrect. I remember having to update my personal website to change the estimated date of the book, and feeling a little sheepish about it every time.”

Anyone who has written a book probably knows that feeling.

But not only did Ellen have the pressure of wanting a book to come out in a timely manner, she was interviewing and writing adjacent to an ongoing FBI investigation. Daedone was eventually convicted on charges of forced labor conspiracy, and in the book we get to hear from Ellen what it was like to be at the trial. Forced labor conspiracy was Daedone’s official crime, but the harm she caused ran much deeper. In the OneTaste world, pain and trauma were repackaged as personal growth, and it doesn’t take a lawyer or a cult expert to understand how quickly that can go wrong.

You can’t read this book without thinking about how many lives were impacted negatively, how a charismatic person and a few enablers can facilitate so much pain and destruction.

In this current political moment, I find myself coming back to the idea that storytelling serves two essential purposes. One is imagination. We need to be able to envision different, more beautiful worlds. In times of darkness, imagination helps us to find the bright spot. The other essential role of storytelling is to tell the truth. To not shy away from the nuances and the complexities, to not obfuscate or apologize, but to shine a light on what is actually taking place. To be clear eyed and report responsibly, calling out harm and injustice when we see it, and holding people accountable.

Ellen’s book does just that, not only painting a picture of what took place at OneTaste, but giving us the context for thinking about how much cult-like thinking is part of our everyday lives.

Thanks to Ellen for having this conversation with me. Pour a big cup of coffee and settle in.

-Anna

Anna Brones: You’re getting as much information as you can, then trying to the best of your ability to pull out the story. But you also have to balance that story with a lens of creativity that helps to make it readable and engaging. What does keeping that balance feel like?

Ellen Huet: I take that so seriously. It really has to be truthful, fair to the best of my ability, and responsible journalism. At the same time it’s a book, it has to be engaging. I love that constraint. That’s why I do this. How can you work with what you know responsibly to be true based on your reporting and make it sing? Make it this thing that people want to keep reading?

There’s a reason I don’t write fiction. It feels like too much possibility. The constraint of what is true is my main creative constraint. I love that. It just works with how my brain works.

You might have a scene, quotes and things that someone says, but you can really land the plane with your own words. That’s where I get pretty excited, thinking about how I can make this scene tee up the next idea that I want to present. Sometimes that doesn’t come from the material. Sometimes that’s just your writing.

I really like that idea of truth as a creative constraint. But it’s a tough constraint isn’t it?

Some people might think, “why would I want that as a creative constraint?” If you are responsible, and the reader knows and trusts you for that, then everything is imbued with a gravitas of it being real. Of course, there’s not a singular truth. But it does imbue it with a seriousness that I find attractive.

“Today’s cults don’t look like they did in the past. Now, they look like mission-driven startups and Fortune 500 companies with demanding schedules and rigid corporate practices. They look like fitness fads, YouTube celebrities, altruistic nonprofits, therapeutic psychedelic guides, and executive leadership training seminars.”

-Ellen Huet, Empire of Orgasm

How does this story fit into our culture currently? What themes are happening in this book that you see taking place elsewhere?

Is there a responsibility to tell this story, not just to document the truth of what took place in the specific organization, but to document the truth about where we’re at in society?

One of the reasons I was drawn to writing this book in the first place is that the subject of OneTaste felt like something I could hold in my hands. It is a scope that fits in a book. But these themes feel really universal, and they feel really applicable to things that are outside of OneTaste: interpersonal manipulation, the changing face of cults, our loneliness and how that makes us vulnerable, the choices that we as humans make under social pressure, tribalism, the draw of what makes us belong, our yearning to understand our sexuality.

The more I learned about cults, the more I realized that they were applicable to so many different parts of my life. I walked into it thinking, “Cults are something that happen to other people.” Now when I look at mission-driven, fast-growth social startups, you can see some of those same dynamics. Obviously, not all the same ones. But this idea of “us versus them,” “insiders versus outsiders.” That’s a really strong dynamic. That is something that keeps people loyal, keeps them in.

Cults change with the times, and they look different now than they did 30 or 50 years ago. People probably have a pretty outdated image of what a cult looks like. Now it’s really different: a YouTube influencer like Teal Swan, or Twin Flames Universe. I’m not specifically saying that those are cults or cult leaders, but you can get this image of how influence looks different now. The more people are aware of that, the more they can protect themselves or their loved ones.

More broadly, as societally we lose trust in institutions, for questions like health guidance, we look to charismatic individuals who say that they have actually figured out a different way. Anytime I see people swapping trust in an institution for trust in an outspoken, charismatic individual, that raises a flag.

This is our national politics right now, isn’t it? You could use this whole book as an example of what is happening on the national stage.

At the beginning of the book you write, “Today’s cults don’t look like they did in the past. Now, they look like mission-driven startups and Fortune 500 companies with demanding schedules and rigid corporate practices. They look like fitness fads, YouTube celebrities, altruistic nonprofits, therapeutic psychedelic guides, and executive leadership training seminars.”

Even if we aren’t in a cult, that language and packaging is part of our cultural vocabulary. What impact does that have on us?

One characteristic of “culty thinking” is that one belief system, one behavior, one school of thought, is going to cure all your problems. This idea that this place, this person, this specific path, is going to be an answer to everything. Think about all the places that you see that. The influencer who’s trying to sell you workshops. The company that’s promising you that if you eat their food, you improve your vitality. That over promise is just an indicator of how widespread this thinking is.

Another rule of thumb that one of my interview subjects told me was, if someone says that they can offer you enlightenment (roughly defined) but they also say that you can only get it through them, then that should be a huge red flag.

It’s fine if people are offering you a solution. Often people do have things that they think will help other people. But if it ever comes tinged with this idea that, “if you don’t get it through me you’ll suffer” or “you won’t find the thing you’re hoping to find” then that’s a real problem. Once you look at it that broadly, you might be surprised at how widely you see that kind of pitch.

This culture of methods, gurus, and influencers who say “I have the one singular answer” feels to me like it’s not possible without this capitalist system that we’re currently in.

One thing I love about the story of OneTaste is Nicole learned this meditative clitoral stroking practice from two predecessor groups. These groups sold courses, that was part of how they made money. But they weren’t so unabashedly commercial. Nicole took that practice, rebranded it as orgasmic meditation, right at the cusp of the wellness boom. She made herself the leader and decided that the way that she wanted to proselytize this practice—which she says was so transformative that she wanted to share it with the world—was by making it a company and a startup.

That seems so strikingly late 2000s, early 2010. Totally girlboss era, wellness boom, startup boom. This idea that startups have a mission.

In the 2010s I was also covering WeWork, whose mission was to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” That was normal at the time. But when you look at it in the rearview mirror, it’s going to look very of the moment. This idea that to proselytize this world changing mission, a startup is the best way to spread the word. Not a nonprofit, not a media company, not anything else.

People wanted to see companies with a woman as the leader. People wanted to have companies that were about wellness, that offered a hack. It was 15 minutes to a better life, basically.

This feels so particularly American. Every single thing—be it spending money, be it assessing your personal trauma—is in service of personal growth. We are steeped in this culture. Individual growth, that’s kind of our number one goal. After having a job that gets you the money to invest in your personal growth, of course.

When I talk to former members, they would tell me that personal growth was used as a rationale for so many pressures. It’s like “oh, okay, so you don’t want to have sex with this person? Well, you should maybe still do it, because that will turn it into an aversion practice, and that’s going to increase your personal growth.” If you’re able to do this hard thing, it’s going to advance your personal growth. You’re totally right that it’s a very American thing.

I was thinking about Nicole’s obsession with edges, and I love edges, but there is a fine balance between the things that are helpful to us and when they start to become harmful. There’s a gray area for a little bit, and it’s probably difficult to assess when it’s gone a little too far in one direction, until you’re at the point where you’re like, “oh shit, this is way too much.”

You say that really well at the end that, where one of your takeaways is that at the wrong place and time, this could have been you. To think that we get out of this just because we somehow have some rationality where we’re not going to participate is an illusion.

I totally agree. A lot of the principles have value to them. I think you should explore your edges. Getting out of your comfort zone can be a good thing for you. And then, there are examples at OneTaste where it’s pretty clear that it has gone too far.

I wish I had some way to summarize where that tipping point is. I don’t know that there is a way to articulate it, but I hope that the book can help people appreciate that spectrum and to understand that there are instances where it really clearly tips into harm.

I wish there was a neater way to say “The takeaway is, if you don’t do these three things…”

That would just be a way to fit it into the packageable advice culture that we have! The takeaway for me reading this book is that there’s never a right or wrong answer. Of course, there are things in this book that are clearly wrong, but in general, we have to appreciate that there’s nuance and spectrum in everything.

But if you had a five step method for how to not get involved in a cult, that’d be a best seller.

I spent so much of my time working on this book creating the narrative product that you’re going to hold in your hands when you buy it. This thing that reads from front to back, that introduces the idea at the pace that I want, with the characters that I think are going to help you remember them. Then once that is done and shipped off, as an author I am expected to think about, “how can I take a few ideas from this book and make them digestible?”

I’m trying to do that in a way that feels authentic and representative of what’s in the book, but it has struck me just how different a task it is. It is not, in any way, the same thing as writing the book.

You have this whole other task of marketing the book.

Absolutely, they’re two different forces, two different jobs. To do each of those, well, you have to be solely in one for a moment.

Yeah, if I were still writing the book, I don’t think I could be thinking about it in this totally other way.

Like we said, this is a very dark topic, and you’ve spent so much time steeped in this. How do you maintain your creative stamina and creative abilities when you’re working on a topic that really could bowl you over? What did you do during the course of working on the book to maintain your own boundaries or sense of separation?

There were periods of time throughout the years where, for various reasons, I would set the book aside for a month or two. Either waiting to get edits from someone or waiting for people to come back to me with notes. I love those fallow periods where you’re like, “I’m just not going to look at this.” I was delighted by the moments when I was back at my draft and would think “Man, I don’t remember writing this.”

People have asked me this question about how do you protect your own mental health as a journalist if you’re reporting on difficult topics? When I have a conversation with someone where they’re really sharing something intimate and difficult with me, it can feel really heavy. But in general, it doesn’t feel hard for me to carry. Even if I’m drained after a conversation, I often feel really in line with my purpose as a witness.

I will feel so honored that someone is willing to talk through me about this thing and to share it through me with a wider audience. I will feel drained, but very fulfilled. This is my current professional purpose: to be a responsible witness and retell this story.

In particular with OneTaste, people would tell me stories about a world that is hard to understand and that people in their outside life—their family, their friends from before they joined—don’t have the vocabulary and the context to understand. Often people tell me, “Oh, you’re the first outsider I’ve spoken to who understands… I don’t have to explain what this jargon means.” And that can feel really meaningful to me, too.

In the moment that OneTaste gains momentum, it’s steeped in the Silicon Valley tech world. I was wondering if you think part of why this became popular is simply because of our need to reconnect with our senses.

We’re continuing to live these flat, digital, desensitized lives that are all on screens. It just gets worse and worse by the day. Do these practices that bring us back into our bodies and reconnect us with our senses have a certain pull to them? While it got taken totally out of control, was OneTaste tapping into a sense of being human? Does that tell us something about what we need to feel good in this world?

Absolutely. Body awareness is even more talked about now than it was 10 or 15 years ago. OneTaste was appealing to people who felt disconnected, who felt “something is missing in my life.” These people felt they were missing connection with other people, connection with their body. The things that OneTaste promised were better relationships, a better connection to your desire and your intuition, better sex. The whole practice was about focusing on how to feel.

I think they were ahead of the curve on what we now see, an increasingly popular framework of having your body being this source of wisdom.

Being on the internet all the time is head only, right? It’s by definition something where you’re not using your body. By the 2010s people were definitely feeling disconnected from themselves, and as a result of that, disconnected from each other, wanting to find a way to feel their body again.

And these are incredibly human things, which is why we’re very vulnerable if somebody sells us an “answer” to these problems.

What made people especially vulnerable to OneTaste’s pitch was that there aren’t that many places where you can go to get answers about sex. So it’s not even just your regular meditation mindfulness, which promises to fix your work/life balance, your relaxation and your stress. This is specifically sold to increase your vitality, your desire, your intuition, but it’s also going to fix your sex life. I think they got people by being willing to go there and to promise that answer in a way that other people just don’t.

Above and beyond OneTaste, why are we culturally so obsessed with cults? Why do you think we are so drawn to a cult story?

They’re extreme but they’re human. It’s a human phenomenon, this idea that we would follow a leader to our own detriment, or that we would join something that we think is going to help us but it harms us.

I think people can recognize that, even if they say to themselves, “Oh, I would never join.” I think people can recognize echoes of themselves, maybe on some level, where they’re curious why someone did it.

Maybe there’s two motivations. One is feeling self righteous: “Oh, I want to see what these other people did. I would never do that.” But I would like to think that subconsciously, people think “I want to understand because maybe I can see a little bit of myself in them.”

People think being in a cult is painful all the time, but it’s not. It’s really fun a lot of the time. That’s what keeps people in.

Okay, last question, which I ask everyone I interview: what does it mean to be creative?

I think it’s as simple as making something that I feel has a reflection of myself in it. Something that feels on some level self-expressive. That’s what feels satisfying and energizing for me. I actually had a conversation with a fellow journalist recently who made a comment that they thought journalism was not creative. I completely respect that it might not feel creative for someone else. But for me, it does. Self-expressive or creative, to me, means: Have I put a little piece of myself in this work?

So what’s the little piece of yourself in this book?

Part of it was a creative challenge: I had done all of the building blocks of it, but never something at this scale. I thought “Okay, this is basically 25 magazine stories.” I’ve done that, but I’ve never done it across a multi-year project. I knew how to write 4000 words, 5000 words, but not 100,000. I knew how to report over the course of six months, but not five years. I was both prepared and unprepared for it, and that felt like the sweet spot.

Other things in the book that feel like they are reflections of me could be as small as certain turns of phrase that are just fun. I recorded the audiobook recently. When I read certain lines, I was like, “I love that line.”

I understand that one of my strengths as a reporter is connecting with sources and building the trust that gets some of these stories to be shared. When I see what materializes in the book, I feel like that’s an expression of something special to me.

Thank you Ellen!

Learn more about Ellen on her website and read her work at Bloomberg. You can support her by buying her book or signing up for her newsletter.

RESOURCES + INSPIRATION

Here is what Ellen has on her radar right now:

Feeding Ghosts by Tessa Hulls. A graphic-novel memoir about Chinese history and intergenerational trauma. I’m halfway through this and loving it so much I’m savoring each sip. I want to make it last as long as possible.

Listers. A documentary ostensibly about competitive birdwatching, but also so much more—brotherhood, stoner humor, bizarre characters, stop-motion animation. Delightful.

This professional animator’s silly Instagram clips. What I love about this account is that the creator has done animation work on big-budget projects like Spiderman and Stranger Things, but his instagram is just hand-drawn clips of Sesame Street characters dancing at the club (or similar scenarios). He explains it simply: “These are on my own time for fun because I love making them!”

Writing in the Deep: Inviting Your Grief to the Page

The world feels heavy right now—and let’s be honest, so do many of our hearts. Grief is a universal truth, something almost entirely inescapable in this life; it’s also a powerful thread of connection and a portal to our most potent and true stories. This winter, join beloved DIVE facilitator Kerri Anne for a timely and emotionally resonant workshop designed to hold space for any deep water you’re ready to explore.

Meets: November 17, November 24, and December 1. More info + tickets.

What We Bring to the Table: A Writing Workshop About Food, Memory, and Meaning

In times of grief, growth, and especially transition, food often becomes the anchor: the way we remember, the way we connect, the way we process what lives beyond our own language. It’s how we pass down stories without words—through spice jars, seed packets, heirloom tomatoes, and the fragrant rituals that fill a dining room. Food connects generations, connects us to the land around us, preserves traditions. Food helps us celebrate and honor the people, places, and flavor profiles that shape our individual and familial stories. Join Kerri Anne for a one-time (for now) notebook-nourishing food-writing workshop designed to help you reflect on the year that’s been—and everything it’s stirred up or shaken loose.

Meets December 8, 15, and 22. More tickets + info.

I am now hooked to the story. I started a BBC four podcast and will watch the Netflix show about it. And obviously buy the book. So intriguing !

What a brilliant interview!!!!